20132ICN337S100_Caso_3

-

Upload

hans-goering -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of 20132ICN337S100_Caso_3

-

7/27/2019 20132ICN337S100_Caso_3

1/12

TETRA TECH EC AND RISK MANAGEMENT

As Don Rogers, chief operating officer of the remediation firm Tetra Tech EC (Tt EC), left the meeting ofproject managers, he reflected on the risk management process he had championed over the last 10 years.Had he gone too far, or not far enough to enhance the companys strategy? He wondered whether the processwas too rigid since it limited innovation, or whether the risk management discipline required by the process

was the reason for the strides in safety and efficiency that had proven profitable to the firm.

COMPANY BACKGROUND

The Electric Bond and Share Company (EBASCO) was founded by Thomas Edison in the early 20th century.Since 1978, it had been owned by ENSERCH Corp. (ENSERCH), an expanding energy company, which hadgrown out of a local distribution gas pipeline company, or LDC, in Dallas, Texas. In 1992, EBASCO found itselffacing increased exposure risks on several Superfund remediation projects, which involved cleaning upenvironmental pollution, including toxic, hazardous or nuclear waste. Prior to 1992, the Superfund projects hadbeen protected from third-party risk for exposure to such hazards through indemnification by theEnvironmental Protection Agency (EPA). However, the EPA was in the process of removing its indemnificationfor remediation projects. This change would expose companies, including EBASCO, to increased risk in this

work.

Several large engineering companies, such as EBASCO, had moved into remediation work because both thefederal government and many U.S. states were concerned about cleaning up the environment and hadinvested resources, either through fiscal policy (i.e. taxes) or by regulating commercial enterprises to ensurethat they reduced their negative impact on the environment. These actions created a context in which theremediation market grew rapidly, with fairly low barriers to entry. Large companies with engineering andconstruction competence, such as EBASCO and Bechtel, were very interested in entering this market since itwas seen to be potentially very lucrative. Yet, the problem with remediation was that it dealt largely withsubsurface contamination: you dont really know what youve got until you start digging. Such unexpectedconditions created economic risk since cleaning up an area could be more costly than anticipated andcontracted for, exposing a company to potentially heavy losses on a project. In 1992, this was the case for

EBASCO, when there were two large remediation projects that were either losing money or about to losemoney:

In the Bridgeport Remedial Oil Services (BROS) Superfund project in southern New Jersey, the contractorwas indemnified for claims of injury or loss to third parties related to environmental pollution. Thisproject involved cleaning up a 500-acre (202-hectare) waste-oil pit site where the owner (a farmer)had accepted, knowingly or otherwise, all kinds of hazardous waste onto his property, which nowneeded to be remediated.

The environmental group at EBASCO had taken on the Times Beach project, a $110-million commercialremediation project, but senior management was very concerned about the potential risk. TimesBeach was founded on a flood plain along the Meramec River in 1925, during a promotion in whichthe now defunct St. Louis Star-Times newspaper gave away properties along the river as part of itssubscription drive. A purchase of a 20!100 foot (6!30 meter) lot for $67.50 included a six-monthnewspaper subscription. In 1971, plagued with a dust problem, due to its 23 miles (37 kilometers) ofdirt roads and lack of pavement funds, the city of Times Beach hired a waste hauler to oil the roads inthe town. From 1972 to 1976, this hauler sprayed waste oil on the roads at a cost of six cents pergallon used. The roads were then paved. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were subsequently foundin the Times Beach soil, and EBASCO was hired to remediate.

EBASCO was facing the possibility of losing tens of millions of dollars on the BROS Superfund project; the

-

7/27/2019 20132ICN337S100_Caso_3

2/12

Times Beach project was in its infancy, but was assessed by senior management as having a high potential tolose money. EBASCO realized that it needed to develop a process that would protect its assets in such anuncertain and risky business. EBASCO hired Don Rogers, the former head of EBASCO Development Co., todevelop a remediation group and manage these projects. His approach, which evolved gradually, involvedmanagement of, rather than avoidance of, risk: take on risk if you can identify it correctly, ensure the properoperational controls are in place, hire competent people to execute the controls and implement a verification

process to ensure that the plan you defined is being executed faithfully.

At the time, EBASCO had an environmental remediation consulting divis ion within EBASCO Services, Inc. anda construction company, which operated as two independent profit centers. Since it took both entities workingtogether to complete the remediation work, Rogers requested that he be made an officer of both companies senior vice-president of Remediation and Construction. The company also instituted a regulatory complianceprogram. A regulatory manager1 was assigned to develop this program. At the same time, personnel changeswere made in the safety program.

During this period, EBASCO was sold to Raytheon. However, since Raytheon did not want to take on the riskassociated with such environmental projects, ENSERCH retained the two groups under Rogers and formedENSERCH Environmental Corp., with the rest of EBASCO being sold to Raytheon. ENSERCH Environmental

Corp. lasted about 18 months and, in the end, thanks to the success of the compliance, safety and riskmanagement programs, was doing about $140 million worth of business annually. Despite this success,ENSERCH decided to focus on gas exploration and distribution, and sold ENSERCH Environmental Corp. toFoster Wheeler in October 1994. Foster Wheeler had a small environmental group (with revenues ofapproximately $60 million per year), which eventually merged processes with ENSERCH Environmental Corp.and became Foster Wheeler Environmental Corp. At that point, Rogers became executive vice-president andchief operating officer (COO) of Foster Wheeler Environmental Corp.

Foster Wheeler Environmental Corp. emerged as a successful company. The management and staff of FosterWheeler Environmental Corp. attributed a significant part of its success to the risk management andcompliance programs. At one point, the head of human resources (HR) at Foster Wheeler approached DonRogers regarding his training programs, but was overwhelmed by their comprehensiveness. The program

appeared to be too big of a deal, and Foster Wheeler decided not to adopt it company-wide. In March 2003,Foster Wheeler sold the assets of Foster Wheeler Environmental Corp. to Tetra Tech (Tt) for $80 million. TetraTech renamed the company Tetra Tech EC (Tt EC), one of approximately 20 different companies owned byTetra Tech. (See Exhibit 1 for the chronology of these events.)

THE EVOLUTION OF THE RISK MANAGEMENT AND COMPLIANCE PROCESS

The elemental steps of the risk management and compliance process that Rogers proposed to ENSERCH in1993/94 was referred to as the Task Initiation Procedure or TIP. At its core, the TIP was as simple asunderstanding the project, identifying the risks and defining the risk management plan for each risk. Since itsearliest inception in 1993, the process included a focus on risks associated with five broad areas and themanagement of the identified risks to be included in 11 planning elements. The five broad areas were

1.site conditions,2.technical performance and how the process of performance and the outcome affect the site,3.stakeholder issues,4.regulatory issues, and

-

7/27/2019 20132ICN337S100_Caso_3

3/12

5.contract issues.The 11 planning elements were

1.the work plan,2.the quality assurance/quality control plan,3.the staffing plan,4.the cost/schedule control plan,5.the communication plan,6.the health and safety plan,7.the status and monitoring plan,8.the risk management plan,9.the documentation plan,10. the cash management plan, and11. the regulatory compliance plan.The approach required the project manager to consider these issues, which focused on identifying the risksassociated with the project being planned.

Once the risk management plan was prepared and approved, the appropriate operational controls for eachidentified risk were included, as appropriate, in one or more of the 11 planning elements listed above. The planwas reviewed by specialists and experts, and approval was needed before the project would be allowed tomove forward. The final stage was to execute the project exactly as it was planned, with any need to deviatefrom the plan leading back in an iterative way to re-planning the project. The mantra in the company was Welike to say we plan our work and work our plan. After projects were up and running, they were regularlyreviewed to ensure that the plans were actually being followed.

The purpose of the Task Initiation Procedure (TIP) was to identify potential risks on a project and developquality objectives and measures, and operational controls and/or mitigations for these risks in a riskmanagement plan. Through this process, environmental aspects that required conformance with theEnvironmental Management System (EMS) were identified, as were design characteristics that required a

technical sponsor to ensure that experts approved work that could be technically complicated. Resourcespecialists, discipline leads, task previewers and TIP approvers were all involved in the process.

The TIP review process began long before a bid was actually placed on a potential contract (see Exhibit 2).Clients typically provided information on a contract approximately six months or more in advance of therequest for proposal (RFP) release. At this time, Tt EC would begin the TIP process. Based on the clientsscope, Tt EC evaluated the risks and communicated this assessment to the client. This information helped theclient to be more precise about expectations when it actually issued the RFP. This early negotiation alsoenabled Tt EC to sell its approach to the client, in hopes of ensuring the client would be more appreciative of

-

7/27/2019 20132ICN337S100_Caso_3

4/12

Tt ECs approach and view of the project risks.

Tt ECs approach meant that business from new clients that were not familiar with this process was oftendifficult to secure; although Tt EC was competitive, it was not typically the low-cost bidder. However, Tt EC hadmore than 90 per cent repeat business because the companies that worked with Tt EC found that Tt EC wasable to deliver on its projects consistently, whereas other companies were not able to deliver as consistently,

possibly because they had failed to identify the risks upfront. On most if not all the projects that Tt EC had lostfor not being the low-cost bidder, the issues of concern that Tt EC had identified in the TIP process becamereal problems for the winning company. For example, on one particular project, Tt EC proposed to excavateand then de-water material before the water was taken off in trucks and disposed of. The competitors bid wasmuch cheaper because it had proposed pumping the material that Tt EC claimed was not pumpable. Thelower priced contractor won the bid. However, the competitor subsequently found that the material couldindeed not be pumped, as Tt EC had predicted. The lower priced contractor could not accomplish the work asintended and, as a result, got in deep trouble on the project. The client turned to Tt EC to complete the project.This example illustrates how the Tt EC approach to risk management created a higher barrier for Tt EC inwinning bids, but nevertheless led to a situation where contracting companies learned to trust Tt EC preciselybecause of its risk management approach.

Given the comprehensiveness of this risk management approach, there was a steep learning curve for new TtEC employees, even those who were very experienced in remediation work. However, once employeesunderstood the TIP and the associated risk management approach, they were able to work on any projectbecause Tt EC does everything the same way.

TT ECS APPROACH TO RISK MANAGEMENT

Tt EC adopted an approach to risk management that was different from most companies. For most companies,a risk appetite decision occurred even before a risk assessment, when the company identified the level andkind of risk it was prepared to take and then assessed whether or not an RFP met its criteria. If the risks werehigher than its appetite, the company would not bid for a contract. However, at Tt EC, the mantra was thatthere is absolutely no risk we cant deal with, even though the company had a very limited risk appetite. Tt

EC was therefore able to take on any risk because the TIP process ensured that a high-risk activity would beconverted to a low-risk activity through the planning process and by implementing operational controls thatwould cope with any problems that might emerge.

There were two aspects to the risk management approach adopted by Tt EC. First, it assessed up-front andtried to both anticipate the risks and identify solutions that would overcome or mitigate those risks. Second, itsbid included a very tight specification of the activities it proposed and included a statement to the effect of

We dont know what is going to happen once we start digging, and our bid is based on the assumptions wehave defined in detail in our offer. If these assumptions hold then we will go with this price. But if they donthold then the scope is different than we have bid, and we will start renegotiating.

In other words, Tt EC mitigated risk by being precise in its bid about what it would do to complete the work at asite, and stated that if it found conditions that were not anticipated and were therefore unable to complete whatit had stated in the bid, then the additional work would be the basis for renegotiating the contract.

Thus, a fundamental aspect of the TIP and risk management approach was that projects were stopped whenthe plan could not be followed. The initial TIP stages meant that a comprehensive plan was necessarilydeveloped. However, every time something unexpected occurred, that aspect of the project was required to bestopped in order to involve the necessary expertise involved. The project then needed to be re-planned beforestarting again. Employees were told that, In the end, it will cost the client and the firm more to continue than if

-

7/27/2019 20132ICN337S100_Caso_3

5/12

you didnt stop and restart.

Stopping and restarting a project could put project managers behind schedule. Thus, many were tempted tosweep problems under the carpet. To avoid this temptation, Tetra Tech EC followed a comprehensiveapproach that began with the hiring process. In orientation training, new hires were taught that slower wasfaster: if you dont stop and re-plan, eventually you will have a problem that you did not plan for, and the

project will take infinitely longer. Also, the teachers/trainers were project managers who could point to theirpersonal experiences. Finally, people were held accountable for the decisions that they made and theprocesses that they used to make them. Employees were told: You would be in more trouble with us if youdidnt stop and plan and made the target than if you did stop and plan and didnt make the target. Thisphilosophy was illustrated in a story that became a legend in the company, when there was a need to enter aconfined space that was not on the original plan. As told by Don Rogers:

Early in the game, we had a Navy project in the northwest. It included a confined space entry. If you have to gointo any confined space, a tunnel, a vessel, a ditch, you go through a protocol, including testing the air andfollowing a sign-off process. We had someone who entered a confined space as a shortcut activity, withoutgoing through the protocol. The person felt comfortable in the confined space, that it was not going to behazardous, expected to get in and out quickly, and in fact, accomplished it. He got in and out quickly without a

problem. We found out about it maybe four or five weeks after the event. The supervisor was not on site at thetime, but got wind of it and raised the flag. It turned out that there was a safety person on the site, who allowedthis individual to do that, and the safety person had called the local office safety supervisor and told them theywere going to let him do it and the safety person supervisor there said okay. We fired the person who enteredthe space; the safety person, who was on site and said it was okay was reprimanded but not fired since he hadsought management input; and the home office person, who said it was okay was also fired. We didnt fire theperson who raised the flag.

Tt EC had three different oversight processes to ensure that projects were working as planned. First, peerreviews occurred during the execution of the work for each stage that resulted in a deliverable or completedsub-project. The peer reviews referred back to the risk management plan to see the risks that were identifiedand the operational controls that were supposed to be executed. The reviewers then determined whether

these controls were being executed. Every project was peer-reviewed by project managers and disciplineleads. Every discipline had peer-review rules. The disciplines wrote their own quality peer-reviewrequirements, which were consistent with regulatory requirements (e.g. 14001 certified). If there were avariation between the planned operational controls and the action that was actually taken, it was consideredperfectly acceptable, as long as the changes were documented, explained and peer-reviewed before beingimplemented.

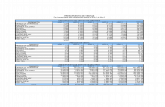

Tier two was project reviews. Every quarter, each project was reviewed by senior management. Whichprojects were reviewed by executives and which were reviewed at the office level were determined by theoffice manager. Projects in excess of $2 million, or high-risk projects, were reviewed by executives. Officemanagers were also required to provide to the executives a sample of projects that were indicative of the workin their office and for which the office manager would like executive input. There was a project review protocol a standard package prepared for the project review. In general, people looked forward to these reviews. TtEC did everything to make them a positive experience and bad news was treated sensitively. The companysphilosophy was: The primary responsibility of executives is to make sure that the person who gives you thatbad news leaves glad they brought you the problem.

Further, project managers found that a quarterly review was not just an opportunity for the executives to lookat the projects and be comfortable that risks were being addressed and customers were being satisfied; it wasalso an opportunity for the project to reach up to the company level and say, I cant execute this part of myproject efficiently because . . . or the IT system needs to be fixed or the procedure doesnt exist to do this

-

7/27/2019 20132ICN337S100_Caso_3

6/12

or we havent been able to hire this staff. Again the value of the project reviews was illustrated in a storyabout a previous project as described by Rick Gleason, vice-president and a senior program manager in theBoston office:

We had a situation three or four years ago on our New England project; we were just gearing up into a verymajor part of work down at New Bedford Harbor, and we needed to hire staff, and we needed some more

emphasis on . . . I think we wanted to implement some slightly different cost and schedule systems, and weactually scheduled a project review and brought some extra people in and had the right discourse at theproject review; got approval from the right areas and support from the right areas to make some hiring, getsome IT [information technology] support, change some systems . . . and thats really when the project reviewworks best. You get both the peer review, kind of that additional layer of protection, but you also have theproject reaching up to the corporate systems and saying, Heres what we need to do our job better.

The third level of review was the audits, which covered both quality and compliance. Projects needed to beshown to be compliant with both the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) and with internal Tt EC systemsand processes. The two audit groups coordinated schedules so that they each reviewed a project once peryear, on a semi-random basis.

The performance of projects bore testimony to the effectiveness of this rigorous TIP and risk managementapproach approximately 98 per cent of the companys work in the last 10 years was completed either on orahead of schedule. The key to this track record was that the schedule changed when the companyencountered a situation that it had not contracted with the client. Clients accepted this approach becauseeveryone in the remediation business was aware that no one really knows what is underground.

IMPLEMENTING THE TIP APPROACH

Don Rogers believed that the critical issue in remediation was managing engineers, construction workers andscientists who tended to be anxious to get on with it, and therefore did not spend enough time in the planningstages. The TIP was introduced to change this mindset. However, the comprehensiveness of the TIP, made itinitially difficult to implement, as recalled by a program manager in Boston:

When we first started these (TIPs) . . . about 1993 . . . those reviews were unpleasant events because you hadproject people thinking that they had all the answers and how dare these people who are both outside theproject and not even necessarily really technical people, who are asking questions that are almost more from alaymans perspective? and this is a waste of my time, and Im doing it just because theyre making me.

However, it soon became clear that even nave questions could promote a discussion that could help identify arisk. The process had evolved so that the project managers generally thought through all the risks whileworking through the TIP. As a result, after the project managers submitted their TIPs for review, reviewers didnot identify many risks that had not been anticipated by the project managers. The TIP on complex projectswas reviewed by a group of reviewers.

Moreover, not only were project managers providing more thorough TIP documents but the reviewers were

also more experienced so that they were less likely to ask off-the-wall, laymans questions. Instead,questions from reviewers were phrased more sympathetically: I realize you may have covered this, but canyou explain it to me? Reviews had, thus, evolved over 12 years from initially being viewed as nasty,contentious, unpleasant, no-value-added procedures to a valuable part of the process that all involvedunderstood and accepted. It was the iterative and the give and take of discussions that appeared to help, asexplained by Jim Leonard, general counsel for Tt EC:

We used to have a TIP reviewer, who prided herself on knowing nothing about these projects. And who asked

-

7/27/2019 20132ICN337S100_Caso_3

7/12

off the wall questions. [She would] say How are you going to do that? and if the project team didnt answerpretty quickly then it was evident that they hadnt thought through how to do it. One example was a very simplejob. There was an old barge the Navy had docked at the end of a pier. There was old residual oil in it and theNavy needed merely to get the oil out of the barge. The Navys proposed scope was, very simple, go get anoil truck, pump it out, take it away and dispose of it. Our nave questioner asked How do you know the pier isgoing to hold the truck after it is full of oil? The team could not answer the question and the reviewers made

the project manager go back and find out. And it turns out the pier wouldnt hold the truck. It was an old pier.So what is the solution? Run a hose out; dont put the truck on the pier. If we had done what the Navy hadsuggested, we could have lost the driver and truck with all that hazardous oil in it. It is one of the things that theprocess does for you. It makes us the least-cost provider [even though our bid may be higher].

In order to ensure that each project was following the Tt EC brand of risk management, extensive training andaccess to corporate procedures were required of all employees. The corporate office provided corporatetraining at three levels: Project Management (PM) 100-, 200- and 300-level courses. The PM 100-level coursewas previously a four-hour in-person module, but had evolved to an online format an initial quickindoctrination into what projects were about. The PM 200-level course was a multiple-day course; two two-dayweekends that covered the Tt EC work process. It included a substantial compendium of training manualsand lectures and hands-on exercises and quiz material. The PM 300-level course was actually beyond the

work process; it focused on advanced issues associated with covering baseline cost- and schedule-management and how to deal with change and notification of change to the client.

EMERGENT ASPECTS OF THE TIP AND RISK MANAGEMENT APPROACH

The risk management approach suggested considerable importance was placed on compliance withregulations, both internal and external. However, over the years, management at Tt EC had found that toomuch regulation, whether imposed or self-imposed, could stifle innovation and interfere with the ability tosatisfy the client. Thus, several years ago, the set of online corporate procedures threatened to overwhelm thecompany. Project managers felt that there were too many procedures, and since project managers were heldfirst and foremost responsible for compliance, there was just too much for anybody to digest and retain foreasy recall. As recalled by Rick Gleason:

For example, our task initiation procedure at the time, and still is for the largest projects, was about a 40-pagechecklist . . . literally a checklist of technology questions, does your project include such-and-such? if yes,have you done this? The idea being, as you work your way through that checklist youll come up with, is therea risk associated with this issue, and if so, what am I going to do about it? It used to be for every project youhad to sort of work your way through about a 40-page document, and even though it was a checklist and itmight have only taken about an hour to go through it, for a small project, people felt like, this is not relevant;not only do I have to fill out the checklist in an hour, but theres probably two or three other hours spent . . . Ihave to send it off for a review, and then I have to incorporate comments, and then we have to get a legalperson and a technical person to come review and approve it, and by the time Im all done, my one hourturned into a four- or five-hour effort, and my overall project is only a week long, or whatever. So now, thereare three or four slightly different permutations, down to the simplest one, which is a page or two of materialthat you look through; you fill it out, and if youre a small fisheries consulting project in the Seattle office, theperson who reviews it is the office manager who has oversight of this project. It used to be everything had togo up to a V.P.-level for review and approval. Now, that particular project is literally a page or two, and thereview is done locally by the office manager, and off you go.

Tt EC recognized the complexity of the process that it had developed and set up working parties to look atsimplifying it. This exercise led to procedures being categorized by discipline. Project managers then had aspecific set of about 10 to 12 procedures that guided them in terms of the must-know, must retain information,as did the engineers, scientists and all other disciplines. Moreover, while the most complex projects involved

-

7/27/2019 20132ICN337S100_Caso_3

8/12

all of the planning elements; for simpler projects, the TIP process has been simplified so that a projectplanner could be used as a simple checklist.

The culture had therefore been nurtured, which encouraged people on projects to identify where theregulations were stifling the ability to conduct the necessary work You have an obligation to raise yourhand and say if I do it the way you are making me do it, it is not going to be optimal. Everything is about

continuous improvement. In other words, the approach recognized that regulations needed to be continuouslyupdated and responsive to changing circumstances. The TIP (and all the other procedures at Tt EC) thereforeincluded a button on the online form that allowed the person preparing the documentation to write an email tothe compliance department, which said I need this variance from this procedure. This statement wasreviewed and could lead either to the project being allowed to vary from the established procedure or to achange in the procedure, where the procedure was considered to be problematic more generally, or to includea better idea:

Its through that constant challenge that makes it relevant, that makes the system work. That is really the heartof the issue. You have got to be willing to say, you know what, filling out this form doesnt make any sense.You have got to be able to say the emperor has no clothes; otherwise, it doesnt work.

The biggest difference between the process in place in 2006 and the process followed initially in the early1990s was in terms of ownership. Initially, the process belonged to the COO who was trying to get people tofollow the process. In 2006, the process belonged to the employees and they changed it all the time. Forexample, during a recent project review out of the Philadelphia office, a detailed discussion ensued about theforecasts and budget models on the website. Attendees admitted that many project managers (including someof the discussants) did not use the model on the website for their forecasts, using self-created spreadsheetsinstead because they found it difficult to import and export information on the website models. Since thewebsite was scheduled for a revision, the project managers wanted to get their remarks heard and decided asa part of the review to hold a brown bag lunch the following month at the Philadelphia office on the use of thewebsite for project managers. The result was that a decision was made to change the website models.

LESSONS-LEARNED METHODOLOGY

Employee moral was high at Tt EC. Employees believed that compliance with the companys risk managementplan and regulatory mandates mattered to the companys success and was rewarded. Human nature was forthe incident person to cover up, but Tt EC required this person to report it. You cant succeed if the personwho identified a problem to you is sorry that he did. You dont know (and therefore cant rectify) what nobodytells you. The importance of reporting incidents was stressed:

We had a terrible compliance violation that hurt the company very badly. It was a really important lesson forme because one of my basic assumptions has always been where you have two people you have safety.One person might break the rules, but with a buddy there, this is less likely. This was a team of five people.The team was working on removing unexploded ordinance from a site. It was Thursday before a 4th of Julyweekend, a long weekend and they were supposed to complete a removal of unexploded ordnance before theweekend began. If you find an unexploded ordnance, there is a protocol you have to use to destroy it. Youbuild a protective facility. If its not clearly marked that there is no fuse on the unit, you have to treat it as ifthere is a fuse and explosive in it. They found not one but many of these things that are not marked andrealized that they would not be able to complete the job. What they should have done, of course, is follow ourrule: stop, re-plan, tell the client we found some new ones and will have to do this again next week, eventhough we are supposed to be finished this week. Instead, they moved this ordnance to a place 100 or soyards away, which would be cleared in the future. What they did when they did that was they moved a piece ofmaterial that is regulated by the range rule. They picked it up and moved it and it became potentially RCRA[Resource Conservation and Recovery Act] waste. Where they put it down became potentially an unlicensed

-

7/27/2019 20132ICN337S100_Caso_3

9/12

RCRA landfill. The five of them conspired to do this. The least experienced person had more than 20 years asa UXO [unexploded ordnance] specialist in the armed services. In the armed services what they did wouldhave been commonplace. They didnt know whether they would do the area they placed this stuff in next ornot, but they knew it was going to be done and they knew there were no explosives in the materials that weremoved. This is in a secure place, protected from the public area. The public cant get into this place. So as faras they were concerned, they did not create a danger. However, they broke serious regulatory rules. Six or

eight weeks later, a disgruntled employee blew the whistle. The employee called the state department ofenvironmental management and brought the state people to that ordinance and showed them that the materialhad been moved. We would have fired all five immediately, but they quit as soon as the event became known.We lost some projects because of this incident because we had a black eye and it cost us about $1.5 million toremedy the problem. What we had to do was go out and survey every piece of work we had done beforebecause the regulatory agency had to assume and not unreasonable of them that this team had done itbefore. We investigated, of course to determine why this happened; to figure out the lesson learned. One ofthe five people turned in the other four, so there were some personal dynamics involved in that process.Candidly, we didnt learn a lot about it. It was probably as simple as it sounds. They wanted to get home totheir families. These guys were working 60-hour weeks. It was the last day before a long weekend. They justwanted to get it done. They thought that they knew enough to be certain they were not causing a hazard. Ithink if they had known what they were doing from a regulatory perspective, they probably wouldnt have done

it. They didnt know there was a whole set of other regulatory criteria that had to be met. One of the correctivelessons we took is we now teach those regulatory requirements in the field. We used to just put them in thework plan. Now we teach them to those who will execute the plan.

Given this background, the company introduced incentives to report incidents and near misses, ranging fromelectronic, formal accolades to t-shirts to spot bonuses. Incident reports were based on a concept from losscontrol in safety management. Perturbations that arose on the job were reported, and a root cause basis forthe perturbation was determined. The incident reports ranged from very simple zero incident performance(ZIP) slips, which were provided online to extensive investigative tools. The ZIP slip was used when there wassomething that was minor enough that it really didnt merit a major investigation, but Tt EC wanted to makenote of it (see Exhibit 3). The idea for the ZIP slip came out of a lesson learned from a Rocky MountainProject.

The person who was involved in the incident did the investigation under the supervision of the technicalsupervisor. To ensure reporting and to ease the paper-work burden, the supervisor aided in filling out theforms, evoking the lesson from the process and documentation. Management continually reminded employeesto look for near misses; report near misses. The rule of thumb was that an incident report should be madeevery 3000 hours: if not, management assumed that it was not being advised of something. Incident reportswere required documentation in project review protocols.

These incident reports were then circulated to other people/projects that would benefit from the knowledge.The supervisor, the quality person and the safety person would make a decision about who owned thisincident, from a technical perspective, called procedure owners. The discipline lead determined who couldbenefit from this lesson and got that lesson to those people, either through e-mails or bulletins (called ZIPbulletins). The system of checks and balances supervisory chain and discipline lead chain was designedto avoid forgetting incidents. Should the manager forget the lesson learned the discipline lead would likely notforget.

Some of these lessons ended up changing work plans and/or procedures. Every two or three days, targetedstaff received an email notice from the administrator saying Procedure Changed. This usually meant severalprocedures had been changed, resulting from either an incident report or a variance request. It was LotusNotes based. We take the old one out and put the new one in. Quite a few companies describe these kind ofthings in their project management and knowledge management processes, but...to do it is rare.

-

7/27/2019 20132ICN337S100_Caso_3

10/12

Lessons learned were proactively distributed by program managers who oversaw several projects. Programmanagers may have spotted things that were worthy of being disseminated throughout the organization as apart of its oversight process. Because program managers were overseeing multiple projects, there was anability to disseminate those lessons learned within the sphere of influence of the individual at the next level.And because they were listening to all of the projects across the country and they were looking for those thingsthat were working well, they were disseminating that information as they moved around the country.

Sometimes the lessons learned were written, and sometimes they were just discussed in the course of havinga review of a project. They would say, You know, on the Rocky Mountain Arsenal project, our folks are doingthis and such, and often they would prompt a write-up on that from the project that they had heard about.Then they would broadcast that information across the company. An example was provided by Rick Gleason:

About two or three months ago, I guess it was, the senior vice-president of Remediation, had sought out fromthe group of us, in advance of the teleconference, the things that we felt were happening under our programsthat were sort of safety best practices. So, there were probably 10 to 12 of us on the call; each of us withinthe domain of our individual programs went in and took a look at what we were doing within those programsthat we thought were a little bit unique, a little bit different, and then, during the course of that phone call weeach had about two or three minutes to lay out we actually gave him an email in advance what we weredoing. One of the things that came out was a remediation project in Corpus Christi, Texas dealing with a fair bit

of work in and around a wetland. It appeared that Hurricane Rita looked like it was going to come ashore in theCorpus Christi area. The team did not have time to return the equipment before the storm hit, so they arrangedthe equipment around the site to be most protective of the materials and supplies. The proactive nature ofwhat they did became a lesson learned and so, the VP asked them to write it up, and then he disseminatedthat to the group of his key program/project managers. Not that were necessarily going to have the sameexperience with the same type of a weather event . . . but the kind of pro-activity is really the lesson learned, ofwhat kinds of things you need to think about and implement before the event, not after the event.

A few years ago, we probably would have made the mistake of saying the contingency plan will include thefollowing fifteen things and will specify the following fourteen things . . . . Weve moved more towards thedirection of the minimum requirement is that you must have a contingency plan. We stop short of saying youmust specifically include in your plan what youre going to do with your equipment and where youre going to

put it, the idea being think about all these things, but put a plan together that makes sense for you.

Ideally, lessons learned become evolutionary by disseminating them and/or writing them and incorporatingthem into the work process. Yet, there is a corporate memory that is also important because it is just notpossible to read 200 Lessons Learned reports and see what is relevant for a particular project. We recognizedthat if you put certain things into lessons learned in writing, they become like everything else these days:discoverable.

-

7/27/2019 20132ICN337S100_Caso_3

11/12

./01213 &

45,.657. 89 .:86;4587 89 4.4? .>

"#$% "##& "##' &((')*+),-./ 0123 )4,+.5 678 -79:;3 +; ?;78@:8A .7;B C7;@:D E:A;F E:GH 0123 I73A:; JH::K:; )8>L

)4,+.5 C;7@ -:@:D?FA?78 F8D .783A;1GA?78 ;:8F@:D E:A;F E:GH ).-:@:D?FA?78 F8D .783A;1GA?78

MMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM"##& "##' "##N 5GAL)4,+.5 AFO:3 78 -F2AH:78 0123 )4,+.5 I73A:; JH::K:; 0123AP7 ;:@:D?FA?78 B;7Q:GA3 R01A 87A -:@:D?FA?78 )*+)-./ )8>?;78@:8AFK

S .783A;1GA?78T ;:8F@:D I73A:; JH::K:; )8>?;78@:8AFK678 -79:;3 8F@:D .55

./01213 @

A>?.,=45> 89 4=AB 57545=4587 !.C;

-

7/27/2019 20132ICN337S100_Caso_3

12/12

Preguntas de Desarrollo

Discutir la evolucin de la gestin de riesgos y el proceso de cumplimiento en Tt CE .Revise el Anexo 2 y analice los componentes del proceso y como esto aporta a lo que respecta a lagestin eficaz del riesgo.Por qu los empleados sienten que son dueos de la gestin de riesgos y el proceso decumplimiento en Tt CE ?Cmo ha sido este proceso ha inculcado en la cultura de la empresa?Hay evidencia de un tono tico a nivel de gestin de Tt CE ? Hable .

Elaborar la evaluacin de riesgos en el proceso de iniciacin de tareas ( TIP) y los procesos desupervisin. Vincula esta discusin con la sensacin de Don Rogers sobre el apetito de riesgo de TtCE.

Comparar y contrastar las lecciones aprendidas del enfoque que Tt CE utiliza en su sistema degestin del conocimiento con el enfoque utilizado por la mayora de las empresas hoy en da .

Qu ha hecho Tt CE para superar las dificultades relacionadas con la aplicacin ERM ? Cmo ha Tt CE superar los desafos que enfrentan las empresas orientadas a proyectos ?

Establecer paralelismos y cita diferencias con estos desafos y los problemas asociados a la gestinestratgica de riesgos (Aydese con lo respondido en la pregunta 4)

-./0102 3

45! 675!

!"#$%&' )&*$+ )&%, -./