manejo trombosis bmj.pdf

-

Upload

john-maynham -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of manejo trombosis bmj.pdf

-

7/29/2019 manejo trombosis bmj.pdf

1/6

doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7535.2152006;332;215-219BMJ

Andrew D Blann and Gregory Y H LipVenous thromboembolism

http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215Updated information and services can be found at:

These include:

Data supplementhttp://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215/DC1

"Further details"

References

http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215#otherarticles6 online articles that cite this article can be accessed at:

http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215#BIBLThis article cites 22 articles, 11 of which can be accessed free at:

Rapid responses

http://bmj.com/cgi/eletter-submit/332/7535/215You can respond to this article at:http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215#responsesfree at:5 rapid responses have been posted to this article, which you can access for

serviceEmail alerting

box at the top left of the articleReceive free email alerts when new articles cite this article - sign up in the

Notes

To order reprints follow the "Request Permissions" link in the navigation box

http://resources.bmj.com/bmj/subscribersgo to:BMJTo subscribe to

on 8 August 2008bmj.comDownloaded from

http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215/DC1http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215/DC1http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215/DC1http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215/DC1http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215#otherarticleshttp://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215#otherarticleshttp://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215#otherarticleshttp://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215#BIBLhttp://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215#BIBLhttp://bmj.com/cgi/eletter-submit/332/7535/215http://bmj.com/cgi/eletter-submit/332/7535/215http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215#responseshttp://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215#responseshttp://resources.bmj.com/bmj/subscribershttp://resources.bmj.com/bmj/subscribershttp://resources.bmj.com/bmj/subscribershttp://resources.bmj.com/bmj/subscribershttp://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/http://resources.bmj.com/bmj/subscribershttp://bmj.com/cgi/eletter-submit/332/7535/215http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215#responseshttp://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215#otherarticleshttp://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215#BIBLhttp://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215/DC1http://bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7535/215 -

7/29/2019 manejo trombosis bmj.pdf

2/6

Clinical review

Venous thromboembolismAndrew D Blann, Gregory Y H Lip

Venous thrombosis is the process of clot (thrombus)formation within veins. Although this can occur in any

venous system, the predominant clinical events occurin the vessels of the leg, giving rise to deep vein throm-

bosis, or in the lungs, resulting in a pulmonary embo-

lus. Collectively referred to as venous thromboembo-lism, these have a high prevalence both in thecommunity and in hospitals, and bring a considerable

burden of morbidity and possible mortality.The causes of venous thromboembolism can be

hereditary or acquired. A risk factor for thrombosisoften can be identified in over 80% of patients, but usu-ally more than one factor is at play in a patient.

Sources and selection criteria

Our information came from a personal collection ofpublished work and searches of Medline using the key

words venous thromboembolism, deep vein throm-bosis, and pulmonary embolus. We also reviewedrecent guidelines on management of venous throm-

boembolism and identified several relevant Cochranereviews.

Deep vein thrombosis

A deep vein thrombosis commonly presents with pain,erythema, tenderness, and swelling of the affected limb.Findings on examination include a palpable cord(reflecting a thrombosed vein), warmth, ipsilateraloedema, or superficial venous dilation. Differentialdiagnoses include a ruptured Bakers cyst, muscle tearsor pulls, and infective cellulitis. Objective diagnosis ofdeep vein thrombosis (as with pulmonary embolism) is

important for optimal management, and although theclinical diagnosis is imprecise, models based on clinicalfeatures are fairly practical and reliable in predictingthe likelihood of an event. Only a minority of patients(less than a third) with suspected deep vein thrombosisof a lower limb actually have the disease.

Compression ultrasonography remains the non-invasive tool of choice for the investigation anddiagnosis of clinically suspected deep vein thrombosis.

Although such imaging is highly sensitive for detectingproximal deep vein thrombosis, it is less accurate forisolated deep vein thrombosis of the calf. The idealmethod, invasive contrast venography, is used when adefinitive answer is required.

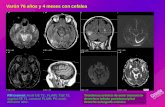

Newer imaging techniques being developed (forexample, magnetic resonance venography, computedtomography) could detect pelvic vein thromboses,

although further testing is necessary to establish theirrole in the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis. Bloodtests such as for fibrin d-dimer, a fibrin degradationproduct, add to the diagnostic accuracy of thenon-invasive tests. d-dimer levels are > 500 ng/ml innearly all patients with venous thromboembolism.

Alone, they are insufficient to establish the diagnosis assuch levels are non-specific and often can be found inpatients admitted to hospital and in those withmalignancy or after recent surgery. Thus, a low or nor-mal d-dimer level with a low pretest probability makesa diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis (or pulmonaryembolism) unlikely. Figure 1 shows a practical

approach to the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosisusing the pretest probability model and a clinicalapproach to diagnosis.

Pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism commonly presents with asudden onset of breathlessness with haemoptysis,pleu-ritic chest pain, or collapse with shock, in the absenceof other causes. Such patients should be investigatedand treated urgently, as pulmonary embolism has ahigh risk of mortality and morbidity. Most patients withpulmonary embolism have no leg symptoms atdiagnosis, with less than a third having signs or

Summary points

Venous thromboembolism, comprising deep veinthrombosis and pulmonary embolism, are

common and treatable in hospital and thecommunity

Major risk factors include age, recent surgery(especially orthopaedic), cancer, andthrombophilia

Established treatments are unfractionatedheparin, low molecular weight heparin,fondaparinux, and warfarin

Treatment agents and duration depend on thecause

Further details and ongoing research are on bmj.com

Haemostasis,Thrombosis andVascular BiologyUnit, UniversityDepartment ofMedicine, CityHospital,BirminghamB18 7QH

Andrew D Blannconsultant clinicalscientist

Gregory Y H Lipconsultantcardiologist

Correspondence to:A D [email protected]

BMJ2006;332:2159

215BMJ VOLUME 332 28 JANUARY 2006 bmj.com

on 8 August 2008bmj.comDownloaded from

http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/ -

7/29/2019 manejo trombosis bmj.pdf

3/6

symptoms of a deep vein thrombus. Conversely, manypatients with symptomatic deep vein thrombosis mayhave asymptomatic pulmonary embolism. A similarclinical model to that for deep vein thrombosis has

been developed for pulmonary embolism. Figure 2summarises the clinical approach to the diagnosis ofpulmonary embolism.

The most common symptoms of a pulmonaryembolus are dyspnoea (73%), pleuritic pain (66%), andcough (37%), whereas the most common signs are tach-ypnoea (70%), crepitations (51%), and tachycardia(30%).3 In severe cases circulatory collapse and cardiacarrest due to pulseless electrical activity may occur. Asinus tachycardia is the commonest abnormality withpulmonary embolism on a 12 lead electrocardiograph,although less often atrial fibrillation, right bundle

branch block, or other features of right heart strain anda S1Q3T3 pattern may be seen.

3 Measurement of fibrind-dimer levels, as for deep vein thrombosis, is helpful.4 5

Pulmonary angiography is the ideal investigation

for pulmonary embolism, but as this is invasive andassociated with 0.5% mortality, a ventilation-perfusionscan is more widely used. A normal perfusion lungscan virtually excludes the diagnosis of pulmonaryembolism. Pulmonary emboli can, however, stillpresent in many patients with low or intermediateprobability scans, and angiography may be needed fora definitive diagnosis. Spiral computed tomogramsusing intravenous contrast (computed tomographyangiography) are more reliable and gaining increasingacceptance for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism.

Who is at risk of venousthromboembolism?

Venous thromboembolism occurs in the community butis a more common complication among hospital

inpatients and contributes to longer hospital stays, mor-bidity, and mortality. In North America each year itoccurs for the first time in around 100 people per100 000. Of these, about one third has a symptomaticpulmonary embolus, the remainder present with a deep

vein thrombus. These rates mask a considerable

variation according to defined populations, such as eld-erly people, rising from fewer than five cases per100 000 children aged less than 15 years to 450-600cases per 100 000 adults aged 80. For those aged 65 andolder, mortality due to pulmonary embolism in hospitaland at one year is 21% and 39% respectively, whereas inthe under 40 years of age group the corresponding ratesfor venous thromboembolism are 2% and < 10%.6

Despite anticoagulant therapy, venous thromboembo-lism frequently recurs in the first few months after theinitial event, with a rate of about 7% at six months,

whereas deathoccurs in around6% of casesof deep veinthrombosis and 12% of cases of pulmonary embolism

within one month of diagnosis. Many of the classic risk

factors for arterial thrombosis (diabetes, smoking) arealso risk factors for venous thromboembolism.7 8

Early mortality after venous thromboembolism isstrongly associated with presentation as pulmonaryembolism, advanced age, cancer, and underlying cardio-

vascular disease. However, lower limb deep vein throm-bosis has been documented in half of all majororthopaedic operations carried out without antithrom-

botic prophylaxis, in a quarter of patients with acutemyocardial infarction, and in more than half of patients

with acute ischaemic stroke. Around 25% to 50% ofpatients with first time venous thromboembolismpresent without a readily identifiable risk factor,although several are recognised and may be classified as

being of high, medium, or low risk (box 1). In a commu-nity study of 1231 consecutive cases of venousthromboembolism, 96% had one risk factor, 76% hadtwo, and 39% had three, the most common risk factors

being aged more than 40 (present in 88% of cases),obesity (38%), a history of venous thromboembolism(26%), and cancer (22%).9

Pathophysiology of venousthromboembolism

What is the link between the risk factors for venousthromboembolism and actual disease? As the basis of

PositiveNegative

Symptoms or signs of deep vein thrombosis

Low pretest probability Moderate or high pretest probability

D-dimer Ultrasonography

NegativePositive

UltrasonographyNo deep veinthrombosis

Negative Positive Positive Negative

No deep veinthrombosis

Deep veinthrombosis

Repeatultrasonography

in one week

No deep veinthrombosis

D-dimerDeep vein thrombosis

For assessment of pretest probability, of suspected deep vein thrombosis:

Score 1 point each for following: tenderness along entire deep vein system; swelling of entire leg,>3 cm difference in calf circumference; pitting oedema; collateral superficial veins; risk factorspresent (active cancer, prolonged immobility or paralysis, recent surgery, or major medical illness)

Subtract 2 points for alternative diagnosis likely (for example, ruptured Baker's cyst in rheumatoidarthritis, superficial thrombophlebitis, or infective cellulitis)

Result: >3=high probability; 1-2=moderate probability; 0=low probability

Fig 1 Clinical approach to the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis. Adapted from Ho et al 1

Box 1 Risk factors for venousthromboembolism

Strong risk factorsFracture of the hip, pelvis, or leg; hip or kneereplacement; major general surgery, major trauma,spinal cord injury

Moderate risk factorsArthroscopic knee surgery; central venous lines;malignancy; congestive heart or respiratory failure;hormone replacement therapy; oral contraceptives;paralytic stroke; post partum period; previous venousthromboembolism; thrombophilia

Weak risk factorsBed rest for more than three days; immobility due to

sitting; increasing age; laparoscopic surgery; obesity;antepartum period; varicose veins

Clinical review

216 BMJ VOLUME 332 28 JANUARY 2006 bmj.com

on 8 August 2008bmj.comDownloaded from

http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/ -

7/29/2019 manejo trombosis bmj.pdf

4/6

venous thromboembolism is inappropriate thrombusformation, then the risk factors would be expected topromote a prothrombotic or hypercoagulable state, asindeed many do.10 Virchows triad refers to threeabnormalitiesabnormal blood constituents, abnor-mal vessel wall, and abnormal flowthat promote

thrombogenesis (thrombus formation). Many predis-posing factors alter one or more components of thistriad.

Idiopathic venous thromboemboli on presentationoften reveal occult cancers at follow-up, such as thoseof the blood, kidney, ovary, pancreas, stomach, andlung.11 12 The risk of venous thromboembolism is alsoincreased by conditions collectively described asthrombophilia, including activated protein C resist-ance, factor V Leiden, protein C deficiency, protein Sdeficiency, antithrombin deficiency, and the pro-thrombin gene mutation 2021A. To these can also beadded increased levels of plasma factor VIII, fibrino-gen, factor IX, factor XI, prothrombin, hyperhomo-

cysteinaemia, lupus anticoagulant, and antiphospho-lipid antibodies.13 14 Furthermore, risk factors interact.The risk of venous thromboembolism in users of theoral contraceptive pill or hormone replacementtherapy is compounded in the presence of factor VLeiden.15 16

Prevention and treatment of venousthromboembolism

To optimise treatment, patients with venous thrombo-embolism should be stratified into risk categories toallow the most appropriate prophylactic measure to beused (for example, for surgery; box 2). Thus theclinician must choose a pharmacological regimen(unfractionated heparin, low molecular weightheparin, warfarin),1719 and also its duration. Predict-ably, in the short term, this may be for only as long asthe particular (transient) risk factor is present, whichmay vary from three to six months. Risks ofhaemorrhage preclude indiscriminate long term use.

Idiopathic venous thromboembolism is generallytreated for six months, but for those with continuingrisk (for example, cancer, immobility, multiple risk fac-tors), anticoagulation may be for life. Many reviews,guidelines, and meta-analyses for thromboprophylaxisin high risk groups are available (box 3).1821 A UKNational Institute for Health and Clinical Excellenceclinical guideline (www.nice.org.uk) on the preventionof venous thromboembolism in patients undergoingorthopaedic surgery and other high risk surgicalprocedures is due to be published by May 2007. TheScottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN)published their guideline on prophylaxis against

venous thromboembolism in 2002 and is awaiting anupdate (www.sign.ac.uk).

As the pathophysiology of pulmonary embolismand deep vein thrombosis is common they are treatedusing broadly similar pharmacological methods andprotocols. In patients presenting with symptomaticdeep vein thrombosis, 50-80% have asymptomatic pul-monary embolism, whereas 80% of patients presenting

with pulmonary embolism will also have an asympto-matic deep vein thrombosis.17 The well knowntreatment with unfractionated heparin, often in combi-nation with warfarin, is slowly giving way to moreeffective and safe compounds.

Low molecular weight heparinThe use of low molecular weight heparin in deep vein

thrombosis and pulmonary embolism is now firmlyestablished. Many trials and meta-analyses haveconfirmed their superior efficacy, safer profile,and cost

PositiveNegative

PositiveNegative

Symptoms or signs of pulmonary embolism

Low pretest probability Moderate or high pretest probability

D-dimer Ventilation perfusion scan or computedtomography pulmonary angiography*

Non-diagnosticNormal High probability

No pulmonaryembolism

Ultrasonographyof leg veins

No pulmonaryembolism

Pulmonaryembolism

PositiveNegative

Pulmonary embolismSerial ultrasonography

Pulmonary embolismNo pulmonary embolism

*A subsegmental defect on ventilation perfusion scanning or a normal first generation helical computed tomogram

should be treated as non-diagnostic

For assessment of pretest probability, of suspected pulmonary embolism: Score 3 points for each of clinical features of deep vein thrombosis and no alternativeexplanation for acute breathlessness or pleuritic chest pain

Score 1.5 points for each of recent prolonged immobility or surgery in previous four weeks,previous history of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism and resting heart rate >100 bpm

Score 1 point for each of active cancer and haemoptysis

Result: >6=high probability (60%); 2-6=moderate probability (20%); 1.5=low probability (3-4%)

Fig 2 Clinical approach to the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Adapted from Lee et al2

Box 2 Risk stratification of thromboemboli forpatients undergoing surgery

Low riskUncomplicated surgery in patients aged less than 40years with minimal immobility postoperatively and norisk factors

Moderate riskAny surgery in patients aged 40-60 years; majorsurgery in patients aged less than 40 years and noother risk factors; minor surgery in patients with oneor more risk factors

High riskMajor surgery in patients aged more than 60 years;major surgery in patients aged 40-60 years with one ormore risk factors

Very high riskMajor surgery in patients aged more than 40 years

with previous venous thromboembolism, cancer, orknown hypercoagulable state; major orthopaedic

surgery; elective neurosurgery; multiple trauma oracute spinal cord injury

Clinical review

217BMJ VOLUME 332 28 JANUARY 2006 bmj.com

on 8 August 2008bmj.comDownloaded from

http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/ -

7/29/2019 manejo trombosis bmj.pdf

5/6

effectiveness over unfractionated heparin. This is partlydue to more targeted action: unfractionated heparinacts on both thrombin and factor Xa about equally,

whereas low molecular weight heparin is more activeagainst factor Xa. The low molecular weight heparinsare, however, different, and trials for one cannot be

extrapolated to another. The introduction of lowmolecular weight heparin has advanced antithrom-

botic therapy by providing effective anticoagulationwithout the need for routine monitoring or adjust-ments, although it can be monitored through ananti-Xa effect. It also allows patients with uncompli-cated deep vein thrombosis to be treated in thecommunity, thus saving an average of 4 or 5 days ofadmission per patient. Low molecular weight heparinhas been shown to be more effective than vitamin Kantagonists (almost all being warfarin) in preventingdeep vein thrombosis after major orthopaedic surgery,

with no significant difference in rates of bleeding.22

Vitamin K antagonistsTraditionally, oral anticoagulants (warfarin being themost widely used) have been the treatment of choicefor long term prophylaxis of venous thromboembo-lism. However, the inappropriate length of timerequired for the therapeutic international normalisedratio to be stable between 2 and 3 demands immediatethromboprophylaxis, as can be provided byheparin.18 19 Once patients are discharged, oral anti-coagulation should be maintained for at least threemonths although longer duration therapy (forexample, six months) is necessary in some circum-stances. Patients without a readily identifiable riskfactor (idiopathic venous thromboembolism) havehigher rates of recurrences that can be reduced by pro-longed anticoagulation, but this must be balancedagainst a corresponding increase in bleeding compli-cations. Current recommendations therefore advocateanticoagulation for at least six months for the firstpresentation of idiopathic venous thromboembolism.Patients with recurrent venous thromboembolism andhypercoagulable states (acquired or inherited) andcancer, should remain receiving anticoagulationtherapy for a minimum of one year and perhapsindefinitely.18

FondaparinuxFondaparinux is a precisely engineered pentasaccha-ride, which binds antithrombin and enhances its activ-

ity towards factor Xa but is devoid of activity againstthrombin. This brings several advantages, such as amore predictable profile, a long half life (17 hours), and

no activity towards platelets. It is at least as effective asunfractionated heparin in treating pulmonary embo-lism,3 23 at least as effective as a low molecular weightheparin in treating deep vein thrombosis,24 with a

benefit over a low molecular weight heparin in riskreduction of venous thromboembolism after ortho-

paedic surgery.25

In one UK health economics study,fondaparinux was more effective and reduced costs tothe healthcare system when compared with a lowmolecular weight heparin.26 An example of recom-mended uses of this and other agents in a definedgroup (mostly after surgery) is shown on bmj.com,although others recommend a different approach inmedical patients.27

Thrombolytic therapyUnlike heparins and warfarin, which prevent extensionand recurrence of thrombosis, the thrombolytic agents(for example, streptokinase, urokinase and tissue-plasminogen activator) lyse the thrombi. Indications forthis therapy are,however,unclear.Recent guidelines18 do

not recommend thrombolysis or thrombectomy fordeep vein thrombosis unless for limb salvage. Similarly,in acute pulmonary embolism these treatments arereserved for the most serious and unstable cases, wherethere is haemodynamic instability.3 Thrombolytictherapy infusion into the pulmonary artery (after clotdisruption using a pigtail catheter manipulated withinthe pulmonary artery) has been reported.28

Non-drug treatmentsCompression stockings and pneumatic compressionhave been used as prophylactic measures against deep

vein thrombosis. Inferior vena cava filters may be usedwhen anticoagulation is contraindicated in patients at

high risk of proximal deep vein thrombosis extensionor embolisation. The filter is normally insertedthrough the internal jugular or femoral vein. Thisapproach should be considered in those patients withrecurrent symptomatic pulmonary embolism and asprimary prophylaxis of thromboembolism in patientsat high risk of bleeding.Other mechanical and surgicaltreatments (for example, embolectomy) are usuallyreserved for massive pulmonary embolism where drugtreatments have failed or are contraindicated.

The future

Since thrombosis is often the final common pathway incardiovascular disease, cancer, and connective tissuedisease, it is not surprising that considerable interest

Box 3 Advantages of low molecular weightheparin over unfractionated heparin

More reliable dose-response relation

No need for laboratory monitoring with theactivated partial thromboplastin time (although can be

monitored with anti-Xa activity) No need for dose adjustments

Lower incidence of thrombocytopenia

No excess bleeding

Can be administered by the patient at home

Economically advantageous

Venous thromboembolism: first steps

When faced with a patient with suspected or actualvenous thromboembolism, relevant sequential stepsare to:

1. Confirm diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis orpulmonary embolism

2. Use established and formal guidelines to considerrisk stratification

3. Decide on treatment (warfarin or low molecularweight heparin, or both)

4. Decide on treatment duration

5. Consider self management or referral to specialistcentre

Clinical review

218 BMJ VOLUME 332 28 JANUARY 2006 bmj.com

on 8 August 2008bmj.comDownloaded from

http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/ -

7/29/2019 manejo trombosis bmj.pdf

6/6

has been shown in the development of new antithrom-botic agents, as shown by the progress fromunfractionated heparin to the low molecular weightheparins and thence, fondaparinux and similar agents.

Although aspirin and clopidogrel have their place, par-ticularly in arterial thrombosis, development of new

anticoagulants focuses on targeting the coagulationpathwayfor example, thrombin and factor Xa. As aclass, the direct thrombin inhibitors (hirudin, ximela-gatran, dabigatran) are beginning to find their place insituations where heparin use is limited, and some mayeventually replace warfarin.29 Like fondaparinux,idraparinux is a heparinoid pentasaccharide, but thelong half-life of the latter (80 hours) means it may begiven once weekly.29

Competing interests: ADB and GYHL have received researchgrants, sponsorship, and hospitality from Astra Zeneca, Glaxo-SmithKline, and Sanofi-Aventis.

1 Ho WK, Hankey GJ, Lee CH, Eikelboom JW. Venous thromboembolism:diagnosis and management of deep vein thrombosis. Med J Aust

2005;182:476-81.2 Lee CH, Hankey GJ, Ho WK, Eikelboom JW. Venous thromboembolism:

diagnosis and management of pulmonary embolism. Med J Aust2005;182:569-74.

3 Stein PD, Terrin ML, Hales CA, Palevsky HI, Saltzman HA, ThompsonBT,et al.Clini cal, laboratory, roentgenographic and electrocardiographicfindings in patients with acute pulmonary embolism and no pre-existingcardiac or pulmonary disease. Chest1991;100:598.

4 Turpie AGG, Chin BSP, Lip GYH. Venous thromboembolism:pathophysiology, clinical features and prevention. In: Lip GYH, Blann

AD, eds.ABC of an tithrombotic therapy. London: BMJ Books, 2003.5 Garcia D, Ageno W, Libby E. Update on the diagnosis and management

of pulmonary embolism.Br J Haematol 2005;131:301-12.6 White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation

2003;107(suppl 1):I4-8.7 Petrauskiene V, Falk M, Waernbaum I, Norberg M, Eriksson JW. The risk

of venous thromboembolism is markedly elevated in patients withdiabetes.Diabetologia2005;48:1017-21.

8 Hansson PO, Eriksson H, Welin L, Svardsudd K, Wilhelmsen L. Smokingand abdominal obesity: risk factors for venous thromboembolism amongmiddle-aged men: the study of men born in 1913. Arch Intern Med1999;159:1886-90.

9 Anderson FA Jr, Spencer FA. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism.Circulation2003;107(suppl 1):I9-16.

10 Lip GY, Chin BS, Blann AD. Cancer and the prothrombotic state. LancetOncol2002;3:27-34.

11 White RH, Chew HK, Zhou H, Parikh-Patel A, Harris D, Harvey D, et al.

Incidence of venous thromboembolism in the year before the diagnosisof cancer in 528 693 adults.Arch Intern Med2005;165:1782-7.12 Petralia GA,Lemoine NR,Kakkar AK.Mechanisms of disease:the impact

of antithrombotic therapy in cancer patients. Nat Clin Pract Oncol2005;2:356-63.

13 Crowther MA, Kelton JG. Congenital thrombophilic states associatedwith venous thrombosis: a qualitative overview and proposedclassification system.Ann Inter n Med 2003;138:128-34.

14 Bertina RM. Elevated clotting factor levels and venous thrombosis.Patho-physiol Haemost Thromb 2004;33:395-400.

15 Wu O, Robertson L, Langhorne P, Twaddle S, Lowe GD, Clark P, et al.Oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, thrombophilias andrisk of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. The thrombosis:risk and economic assessment of thrombophilia screening (TREATS)study. Thromb Haemost2005;94:17-25.

16 Gomes MP, Deitcher SR. Risk of venous thromboembolic disease associ-ated with hormonal contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy: aclinical review.Arch Inter n Med 2004;164:1965-76.

17 Buller HR, Sohne M, Middeldorp S. Treatment of venous thromboembo-lism.J Thromb Haemost 2005;3:1554-60.

18 Hirsch J, Guyatt G,Albers G, Schunemann JH, Munger H, Brower S,et al.

Seventh ACCP conference on anti-thrombotic and thromboembolictherapy. Chest2004;126(suppl 3):S172-696.

19 Haemostasis and Thrombosis Task Force of the British Society forHaematology. Guidelines on anticoagulation: third edition. Br J Haematol1998;101:374-87.

20 Ost D, Tepper J, Mihara H, Lander O,Heinzer R,Fein A. Duration of anti-coagulation following venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. JAMA2005;294:706-15.

21 Lee AYY. Management of thrombosis in cancer: primary prevention andsecondary prophylaxis.Br J Haematol 2004;128:291-302.

22 Mismetti P, Laporte S, Zufferey P, Epnat M, Decousus H, Cucherat M. Pre-vention of venous thromboembolism in orthopaedic surgery with vitaminK antagonists: a meta-analysis.J Thromb Haemostas2004;2:1058-70.

23 Buller HR, Davidson BL, Decousus H, Gallus A, Gent M, Piovella F, et al.Subcutaneous fondaparinux versus intravenous unfractionated heparinin the initial treatment of pulmonary embolism. N E ngl J M ed2003;349:1695-702.

24 Buller HR, Davidson BL, Decousus H, Gallus A, Gent M, Piovella F, et al.Fondaparinux or enoxaparin for the initial treatment of symptomaticdeep venous thrombosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med2004;140:867-73.

25 Turpie AG, Bauer KA, Eriksson BI, Lassen MR. Fondaparinux vs enoxa-parin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in majororthopedic surgery: a meta-analysis of 4 randomized double-blind stud-ies.Arch Inter n Med 2002;162:1833-40.

26 Gordois A, Posnett J, Borris L, Bossuyt P, Jonsson B, Levy E, et al. Thecost-effectiveness of fondaparinux compared with enoxaparin asprophylaxis against thromboembolism following major orthopedicsurgery.J Thromb Haemost2003;1:2167-74.

27 Wolozinsky M, Yavin YY, Cohen AT. Pharmacological prevention ofvenous thromboembolism in medical patients at risk. Am J CardiovascDrugs 2005;5:409-15.

28 Wong PS, Singh SP, Watson RD, Lip GY. Management of pulmonarythrombo-embolism using catheter manipulation: a report of four casesand review of the literature. Postgrad Med J1999;75:737-41.

29 Weitz JI, Bates SM. New anticoagulants. J Thromb Haemostas 2005:3;1843-53.

(Accepted 22 December 2005)

Additional educational resources

Useful websiteCenter for Outcomes Research (www.dvt.org)usefulinformation for professionals, with links to other sitesand access to some research papers

Information for patientsInvestigators against thromboembolism(www.inate.org)useful website for professionals andpatients, with links to other sites

www.heartonline.comuseful website for professionalsand patients, with information on cardiovasculardisease and its risk factors and links to other sites

So, those who cant do it, teach it?

It has been said that He who can, does. He who cannot, teaches.I have often wondered whether there is any truth behind thisfrequently quoted expression, which surgical students hear fromthe early days of their clinical training. To find the answer, onemust look at the origin of the phrase itselfback to the Ir ishplaywright George Bernard Shaw (1903). Shaw, however, wasreferring to revolutionaries, not teachers. The phrase is, therefore,used out of context.

Most of us, looking back over our training, can attribute ourchoice of specialty to one or more mentorsteachers soenthusiastic and inspirational that they instilled within us thedesire to better ourselves and thereby better serve our patients.

They taught us to think for ourselves. Most of us will also admitthat these inspiring individuals were not just devoted teachers but

had notably inquiring minds and were almost always exceptionalclinicians.

Charles H Mayo (1865-1939), one of the founders of theinternationally renowned Mayo Clinic, once said: The safestthing for a patient is to be in the hands of a man involved inteaching medicine. In order to be a teacher of medicine thedoctor must always be a student. Therefore, the next time youhear Shaw quoted out of context, perhaps you might respond byquoting Mayo, a man described not only as an inspirationalteacher but also as a surgical wonder.

Perhaps those who dont teach it cant do it as well as theythink.

Farhad B Naini consultant in facial deformity, St Georges Hospitaland Medical School, London ([email protected])

Clinical review

219BMJ VOLUME 332 28 JANUARY 2006 bmj.com

on 8 August 2008bmj.comDownloaded from

http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/http://bmj.com/