pb_exitstrategies_151009_01

Transcript of pb_exitstrategies_151009_01

-

8/6/2019 pb_exitstrategies_151009_01

1/8

A EUROPEAN EXITSTRATEGY

bruegelpolicybriefISSUE 2009/05OCTOBER 2009

by Jrgen von HagenNon-resident Senior Fellow at Bruegel

Professor of Economics, University of Bonn

Jean Pisani-FerryDirector of Bruegel

and Jakob von WeizsckerResearch Fellow at Bruegel

SUMMARY As economic growth resumes, a timely exit from the currentcrisis mode of unsustainable budgetary, monetary and financial sector

policies is needed. Yet, the exit must not be rushed or we risk a relapse intoanother recession. We propose a sequence of steps towards the exit whichshould be closely coordinated at European and, where possible, global levelover the coming months. Furthermore, in order to ensure that this exitstrategy is credible and does not prove to be an empty promise of consoli-dation, we suggest institutional arrangements within the EU that wouldprovide incentives to follow through.

POLICY CHALLENGE

First, the identification and recapitalisation of ailing banks must be com-

pleted urgently, with a clear timetable for the phasing-out of state support.Second, member states should adopt medium-term sustainability bud-getary plans in summer 2010 to be implemented from 2011. These plansshould detail annual minimum and maximum consolidation objectives aswell as a debt target for 2014. Third, monetary policy should remain as sup-portive as possible. Fourth, given continuing low interest rates, and in order

to supervise phasing-in ofmore stringent financial reg-ulation, the plannedEuropean Systemic Risk

Board should become opera-tional as early as summer2010. Finally, to ensure thenecessary coordination ofthe exit between memberstates and central banks, anad-hoc reinforced consulta-tion mechanism should beset up at European level for2.5 years, renewable once.

0% -1% -2% -3% -4% -5%75%

80%

85%

90%

95%

100%

105%

110%

Crisis-related one-time loss in potential output, percent of GDP

Debt-to-GDP ratio in 2020 with minimum

consolidation speed of GDP

Euro area

EU27

Projected debt to GDP ratio in 2020 assumingannual consolidation of 0.5% GDP*

* As a function of one-time loss in potential output due to the crisis.

Source: Bruegel simulation, see Figure 4

-

8/6/2019 pb_exitstrategies_151009_01

2/8

bruegelpolicybrief02

A EUROPEAN EXIT STRATEGY

EU-27 Euro area DE IT PL FR ES UK

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

2010

2009

2008

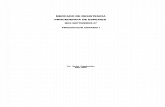

Figure 1: Surging deficits in response to the crisisCumulative budget deficits 2008-2010 as a percentage of GDP in 2010

Source: IMF (2009b) except for Poland: IMF Article IV Report, August 2009.

1. This policy brief sum-marises and updates a

paper prepared at therequest of the SwedishEU Council presidencyfor the ECOFIN Council

of 1 October 2009.Research assistance byMartin Kessler is grate-

fully acknowledged.

2. See for exampleCerra and Saxena,

2008, Pisani-Ferry andvan Pottelsberghe,

2009, and IMF, 2009b.

an increase in the structuralbudgetary deficit.

Monetary policy has broughtinterest rates down to nearly zerofor all major currencies, includingthe euro. In addition, central-bankefforts to rescue financial systemsby giving banks easier access tocentral-bank money has caused arapid and signicant expansion,and changes in the composition, ofbanks balance sheets. So far, thispolicy of quantitative easing and

qualitative easing has not affect-ed the broad money supply andtherefore not resulted in inflation-ary pressures (von Hagen, 2009).But, as banking systems recover,central banks must keep a keeneye on monetary developments toensure that inflationary potentialdoes not build up in the future.

Governments have also supportedbanking systems directly through

guarantee schemes and recapitali-sation. These measures have suc-ceeded in restoring some financialstability. However, the most recentestimates of the necessary write-downs in the banking sector(Figure 2) suggest that recapitali-sation has not to date been suffi-cient. Available evidence (IMF,2009c) indicates there are signifi-cant differences across countriesand across banks, which suggests

targeted action at national level isstill required.

So far, European governmentshave focused on emergency meas-ures to prevent collapse of thefinancial system without fullyaddressing the fundamental issueof undercapitalisation of thebanks. Meanwhile banks are bor-rowing at near-zero interest ratesand investing in higher-yielding

ence of exit-policy instrumentsand what this implies. The fourth

section develops a sequenced exitstrategy and discusses its imple-mentation. The fifth section sum-marises the policy recommenda-tions.

THE POST-CRISIS LANDSCAPE

One year after the acute crisisstarted in Europe, monetary andfiscal policy are operating in crisismode. The resulting surge in bud-

get deficits (Figure 1) is unprece-dented in the EU. As a conse-quence, the IMF (2009a) projectsan increase in the average debt-to-GDP ratio in the euro area of 30percentage points, to reach 90percent of GDP by 2014. This aver-age disguises substantial increas-es for some member states.

Part of the budgetary deteriorationis cyclical, but part is permanent.

In the years following a shock, growth rates often recover to thepre-crisis pace but the loss in out-

put level typically remains perma-nent2, implying a correspondinglasting shortfall in governmentrevenues. As a result, there will be

THE CURRENT BUDGETARY, mone-tary, and financial-sector policies

have been emergency measuresto cushion the initial blow of thecrisis and to prepare the road torecovery. But these emergencymeasures are not sustainable inthe long run and must be phasedout. Finding the right exit strategyis difficult. How fast can andshould normalisation take place?How should budgetary, monetaryand financial-sector policies besequenced? And should these

steps be coordinated within theeuro area, the EU and beyond inorder to avoid adverse macroeco-nomic developments? To compli-cate matters further, the task isnot only to return to the normalstate of the economy before thecrisis. As a result of the crisis andof the lessons to be learned from it,'normality' in the future will haveto be different from pre-crisisbusiness as usual.

This policy brief addresses thesequestions and outlines an exitstrategy for the EU1. The secondsection looks at the conditionscurrently confronting us. The thirdsection explores the interdepend-

-

8/6/2019 pb_exitstrategies_151009_01

3/8

A EUROPEAN EXIT STRATEGY

bruegelpolicybrief03

3. The output gap is thedifference between

potential output andactual output.

United States Euro area Rest of western Europe

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

Realised writedowns or loss

provisions: 2007:Q2 - 2009:Q2

Expected additional writedowns or

loss provisions: 2009:Q2 - 2010:Q4

Figure 2: Reported and estimated potential write-downs in the banksector(in percent of GDP)

Source: IMF (2009c). Note: rest of western Europe includes Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Sweden,Switzerland and the UK.

assets, which is allowing them toregain better profitability and tostrengthen their capital base. Thisprocess could go on for as long asit takes for them to reach thecapital ratios required byregulatory and, perhaps moreimportantly, market standards.

However, in the meantime itinvolves the risk of relapse intoinstability in the banking sectorand persistent constraints on thesupply of credit. In view of this, itwould be unwise to undertake thenecessary fiscal and monetarypolicy exit without first addressingthe remaining problems of thefinancial sector.

POLICY INSTRUMENTS AND

STRATEGIC INTERDEPENDENCE

An appropriate exit strategy musthave at least three broadobjectives:

i The restoration of budgetarysustainability,

ii Macroeconomic stability withnon-inflationary growth at apace compatible with elimina-tion of the output gap3 in the

medium term, andiii Financial stability, which

implies both stability of the

Note: macro-prudential oversight is categorised here as belonging to central banking because it isassumed that, following European Council decisions in June, it will largely be done by central banks.

Table 1:Dimensions of exit from exceptional crisis-management measures

Institutional actor

Governments Central banks

Impacton

Macro Budgetary consolidationMonetary tightening (reversequantitative easing, increase

interest rates from near-zero level)

Banks

Withdrawal of governmentguarantees for banks;

Bank triage, recapitalisation andrestructuring

Withdrawal of liquidity supportfor banking sector;

Macroprudential oversight

Table 2:Direct and indirect impact of exit policies on exit and other major objectives

(Direct impact in red) Impact on exit objectivesBudgetary

sustainabilityMacro

stabilityFinancialstability

Potentialoutput

Exitpolicies

Budgetary consolidation + - +/-

Monetary tightening - -/+ +/-

Withdrawal of liquiditysupport

+ - - -

Withdrawal of governmentguarantees

+ - - -

Otherpolicies

Bank recapitalisation andrestructuring

-/+ + +

Macroprudential oversight + + 0

financial sector without govern-ment or central-bank support

and the prevention of financialinstability in the future.

The pursuit of these exit objectivesinvolves budgetary consolidation,monetary tightening and the with-drawal of guarantees and excep-tional liquidity support for banks.Table 1 shows the various policyinstruments involved in the subse-quent exit discussion.

However, each of these policyactions has both direct and indi-rect effects that should be takeninto account when designing anexit strategy. Table 2 provides astylised summary of the likelydirect and indirect impact of exit

-

8/6/2019 pb_exitstrategies_151009_01

4/8

bruegelpolicybrief04

A EUROPEAN EXIT STRATEGY

policies on the exit and other majorpolicy objectives.

It is instructive to explore theseeffects in detail, starting with theimpact of budgetary consolidation.While its direct impact onbudgetary sustainability will nor-mally be positive, budgetary con-solidation would tend to reduceeconomic activity, especiallywhere consolidation relies onincreasing tax rates. Such a reduc-tion in economic activity would

tend to reduce inflation and nega-tively affect the health of thefinancial sector, not least becauseof increased default risks. Finally,the impact on potential outputdepends on the quality of theadjustment programme, so it isambiguous.

The impact of monetary tighteningis similar to the impact of bud-getary consolidation, so to some

extent they can be thought of assubstitutes. But there are twoimportant differences. First, whilethe impact of budgetary consolida-tion on price stability tends to bepositive, the indirect impact ofmonetary tightening on debt sus-tainability tends to be negative,both on account of an increasedoutput gap and of higher realinterest rates on legacy debt.Furthermore, the impact on

financial-sector stability of mone-tary tightening is ambiguous.While monetary tightening tends toreduce financial-sector profitabili-ty, thereby increasing the vulnera-bility of ailing banks, real interestrates close to or even below zeroincrease the likelihood of disruptiveasset bubbles. By reducing the riskof the re-emergence of bubbles, in-creased interest rates thereforealso improve financial stability.

The withdrawal of liquidity supportfrom the banking sector reduces

the budgetary and quasi-budgetary exposure to bankingrisks, thereby helping to improvebudgetary sustainability. However,the positive budgetary impactmight be inhibited if this very with-drawal increases the risk offinancial-sector instability.

So: all core exit policies couldtherefore negatively impact notonly economic activity but also

financial-sector stability. Thisimplies a strategic interdepend-ence between these instruments,meaning simultaneous and vigor-ous pursuit of all three exit policiesmight entail a serious risk of a dou-ble-dip recession and a renewedcrisis in the banking sector.

Fortunately, the risk linked to thisstrategic interdependence can bemitigated somewhat by the pur-

suit of complementary policies(other policies in Table 2). Bankrecapitalisation and restructuringand macroprudential oversight areadditional instruments for reach-ing the policy objectives.

DESIGNING AN EXIT STRATEGY

The European Council of 18-19June concluded that there is aclear need for a reliable and credi-

ble exit strategy, inter alia byimproving the medium-term fiscalframework and through coordinat-ed medium-term economicpolicies.

A prerequisite:complete the recapitalisation andrestructuring of ailing banks

Identification, recapitalisation andrestructuring of ailing banks, not

fiscal retrenchment, should be thefirst step in the exit strategy. Once

accomplished in full, it will allowcentral banks and ministers offinance to pursue their futuremonetary and budgetary exitswithout the constant fear of caus-ing renewed bank failures in theprocess. Furthermore, attending tobanks first will boost recovery bymaking credit more readily avail-able to business and enhancinglonger-term growth prospects atthe same time.

International interdependence isat work here, especially within theeuro area: in countries where bigbanks remain insecure and de-pendent on exceptional liquidityprovision at near-zero interestrates, lack of action by treasuriesrepresents a de-facto constrainton the ECBs freedom of action.

But the recommended swift bank

recapitalisation is easier said thandone. The main difficulty is that itis hard to make the case to elec-torates angry at the financialsector. It should be argued force-fully that delaying recapitalisationis likely to be even more costly, asthe example of Japan illustrates.Also, it should be pointed out thatrecapitalisation can even be aprofitable investment, as was thecase in Sweden. In addition, proper

incentives for member states notto delay recapitalisation should beprovided. First, credible deadlinesshould be set regarding the phas-ing out of government guaranteesat the European level, using EUstate-aid rules to enforce it.Second, central banks may wish todesign their exit from bank sup-port measures along a similartimescale. This is possible sincethere are no compelling reasons to

-

8/6/2019 pb_exitstrategies_151009_01

5/8

A EUROPEAN EXIT STRATEGY

bruegelpolicybrief05

4. The stress-testresults made public bythe CEBS on 1 October

2009 include almost noinformation on the dif-

fering situations acrosscountries and across

banks. They thereforefail to provide sufficient

guidance.

0% -1% -2% -3% -4% -5%75%

80%

85%

90%

95%

100%

105%

110%

Crisis-related one-time loss in potential output, percent of GDP

Debt-to-GDPratioin2020withminimum

consolidationspeedofGDP

Euro area

EU27

Figure 3: Projected debt to GDP ratio in 2020 assuming annual consolida-tion of 0.5% GDP*

* As a function of one-time loss in potential output due to the crisis. Source: Bruegel simulations, seeBox 1 (overleaf).

0% -1% -2% -3% -4% -5%0.4%

0.6%

0.8%

1.0%

1.2%

1.4%

1.6%

Crisis-related one-time loss in potential output, percent of GDP

Consolidations

peedi

n%o

fGDPp

ery

ear

Required consolidation rate

EU-27 average

Required consolidation rate

Euro-area average

SGP minimum consolidation rate

Figure 4: Consolidation rate required to reach a 75 percent debt-to-GDPratio in 2020*

* As a function of one-time loss in potential output due to the crisis. Source: Bruegel simulations, seeBox 1 (overleaf).

link the timing to that of the otheraspects of the monetary exit,

especially macroeconomic nor-malisation (see for example BiniSmaghi (2009), Trichet (2009)and Bernanke (2009)). Third, therequirements of the excessive-deficit procedure should be adapt-ed to accommodate bank recapi-talisation. This could be achievedby temporarily calculating thebudgetary cost of bank rescue netof the value of the bank sharesgovernments receive in return.

Once that arrangement expires, forexample in 2014, the return to theusual Maastricht definition of thedebt would serve as a welcomeincentive not to unduly delay pri-vatisation. Lastly, comprehensivestress-testing and a framework forwork-out at the European levelwould be highly desirable (seePosen and Vron 2009 for adetailed proposal)4.

The first macro step: budgetaryconsolidation

Budgetary consolidation shouldcome before monetary tightening,mainly because fiscal policy is themore costly and less nimble stim-ulus instrument. Besides, delayingconsolidation or leaving its paceand duration hanging in the airwould involve a non-trivial risk ofadverse bond-market reaction.

Finally, successful budgetary con-solidation will reduce inflationarypressures, thereby allowing cen-tral banks to sustain a supportivemonetary policy stance for longerand tighten monetary policy onlywhen inflationary potential arises.This sequencing, rather than mon-etary tightening first andbudgetary consolidation second,should be a priority goal in thedesign of exit strategies.

least because of the rapidlyincreasing budgetary cost of age-ing populations.

By way of illustration, Figure 4shows that the annual consolida-tion speed might have to be signif-icantly above the minimum rate of

the SGP if the objective were toachieve a debt-to-GDP ratio of 75percent on average across the EU.(The challenge of consolidationwill be greater still for a number ofindividual EU countries inside andoutside the euro area).

Figure 3 shows the extent to whichthe budgetary outlook has wors-ened during the crisis. According toour simple fiscal simulation, thedebt-to-GDP ratio for the EU27could still stand at 100 percent ofGDP in 2020, even assuming a fullwithdrawal of the stimulus pack-

ages in 2011 and a budgetary con-solidation rate of 0.5 percent ofGDP per annum thereafter, which isthe minimum consolidation speedrequired by the EUs Stability andGrowth Pact (SGP). This debt levelcould be unacceptably high, not

-

8/6/2019 pb_exitstrategies_151009_01

6/8

A EUROPEAN EXIT STRATEGY

bruegelpolicybrief06

5. This is also the con-clusion of Cottarelli and

Vials (2009).

6. These conditionsincluded inter alia

strong externaldemand, initially high

levels of long-terminterest rates (whichdropped as a conse-quence of consolida-tion), and monetary

support (lower interest-rate and exchange-rate

depreciation inresponse toconsolidation).

7. In this process ofnormalisation, central

banks should continuetheir past practice offocusing on second-

round effects ofincreases in world

market prices of rawmaterials and agricul-

tural produce if andwhen they arise as theglobal economy starts

to pick up again.

BOX 1: KEY ASSUMPTIONS OF THE FISCAL SIMULATION

The fiscal simulation underlying Figures 3 and 4 uses the most recentdata and forecast of the European Commissions DG ECFIN for the EU27as a starting point. It then assumes a 1.5 percent growth rate ofpotential output until 2020, a linear narrowing of the output gap until itreaches zero in 2015, and a real interest rate for public borrowing of 2.5percent.

On that basis, the evolution of the debt-to-GDP ratio is extrapolateduntil 2020 as a function of two key parameters: the one-time loss inpotential output due to the crisis and the speed of budgetary consoli-dation. Specifically, a one-time hit to potential output in 2010 varyingbetween 0 percent and 5 percent of potential GDP is considered. The

consolidation is modelled assuming that discretionary stimuli are sus-tained in 2010, fully discontinued in 2011 and as of 2012 varyingspeeds of consolidation are applied. For example, at a consolidationspeed of 0.5 percent of GDP, the primary budgetary position isimproved by an additional half percent of GDP every year until thebudgetary surplus reaches 1 percent of GDP. After that, the structuralexpenditure and revenue ratios are kept constant.

that should be adopted by nationalparliaments by summer 2010.Reforms that improve public-finance sustainability in the medi-

um run, notably pension reforms,should be taken into account in thesetting of budgetary objectives.With these comprehensive prog-rammes, member states shouldcommit to a minimum speed ofconsolidation and to debt-ratiostabilisation by 2014 at the latest.

While budgetary consolidationmust be swift, it should not beabrupt. The multiple impact of sig-

nificant and simultaneous re-trenchment in most EU countries(and beyond) is likely to representan important drag on demandgrowth. The conditions that in thepast allowed some countries toexperience painless consolidationare unlikely to be met6. Thus, theproposed national SustainabilityProgrammes should not only pro-vide a minimum but also a maxi-mum envisaged speed of consoli-

From these simulations we canconclude that the budgetary con-solidation required will be sub-stantial on average5. In order to

make this politically delicate andpainful process credible and suc-cessful, a strong collective com-mitment is needed at Europeanlevel over and above the provi-sions of the SGP. Although the Pactis not the answer to the consolida-tion challenge, as officials tend toclaim, it should not be weakened inthe process but rather used as aninstrument to achieve sustain-ability. This is by no means trivial

since we are in uncharted territo-ry: today, as many as 20 memberstates out of 27 find themselvessubject to the SGPs excessive-deficit procedure.

The primary focus should be onrestoring the sustainability of pub-lic finances. The larger the debtratio, the faster consolidationshould be, enforced via medium-term Sustainability Programmes

dation, and their implementationshould be jointly monitored.

Implementation could be coordi-nated by the Eurogroup for theeuro area whereas the EUs ECOFINCouncil (for EU-wide coordination)and the G20 (for global coordina-tion) should also play their roles.

The credibility of government com-mitments to sustainable publicfinances is the key to successfulconsolidation. We recommend thatgovernments establish

Sustainability Councils at thenational level with the task of mon-itoring the development of publicfinances, advising governmentson strategies to reduce debt andgiving public comments on, andassessments of, their countriespublic finances (see Pisani-Ferryet al, 2008). Countries with moreeffective institutions or effectivefiscal rules and stronger trackrecords should be given more flexi-

bility in implementing their com-mitments. Member states shouldalso consult on reforms which canhelp offset the decline in potentialoutput resulting from the crisis,and which strengthen potentialoutput growth in the medium term.They should start to implementthese commitments in 2010 andthey should be prioritised in theforthcoming update of the Lisbonstrategy, the EUs own mid-term

economic-strategy template.

Monetary policy: arms-lengthsupport

If budgetary policy is given prece-dence, the implication is that, con-sistent with central banks man-dates, monetary policy shouldremain geared to price stabilityand would normalise once justifiedby expected price developments7.

-

8/6/2019 pb_exitstrategies_151009_01

7/8

A EUROPEAN EXIT STRATEGY

07

bruegelpolicybrief

8. 24-25 September2009, see http://www.

pittsburghg20.org

is therefore advisable to establishtemporary arrangements for coor-

dination, with a sunset clause. Werecommend that EU governmentsand central banks commit to coor-dinating exit strategies and set upunder Article 100 (1) of the treatya temporary (say two-and-a-halfyears, renewable once) reinforcedconsultation mechanism. Thisshould commit governments to ex-ante consultation with the Comm-ission and partners on all aspectsof exit strategies and should

include a joint political commit-ment to make use of country-specific recommendations in thecase of departure from the com-monly agreed strategy.

With such a temporary EU coordi-nation framework in place, it willalso be easier to develop coopera-tive and coordinated exit strate-gies at the global level as calledfor at the Pittsburgh G20 summit8.

G20 cooperation would need toinclude discussion of exchange-rate developments, in particularwith the US and China.

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

On the basis of the above analysis,we recommend the following:

1. In recognition of the exception-al character of the situation, EU

governments and central banksshould commit to coordinatingexit strategies and set up areinforced consultation mecha-nism to this effect.

2. Bank recapitalisation and re-structuring should be complet-ed in all EU countries urgently.Until the end of 2014, assess-ments of member states bud-getary situations and budgetaryconsolidation plans should be

they might consider at odds withtheir independence and their

mandate. And substantively, cen-tral banks focused on inflationmight well like rapid budgetaryconsolidation more than govern-ments with their minds on short-term growth and employment. Thiscould lead to a situation where agovernment go-slow on budgetaryconsolidation provokes centralbanks into a headlong dash formonetary tightening.

Against this background we rec-ommend that, at the technicallevel, efforts be intensified to forma consensus view between mem-ber states and central banks onwhere potential output currentlystands and how it is likely toevolve. And at the political level,budgetary authorities will be welladvised to internalise to someextent the often more hawkish exitpreferences of the central banks to

assure that the desired sequentialexit can take place.

Governments and central banksshould keep each other abreast oftheir intended policies and eachtake into account the plans of theother. In particular, the ECB shouldbe very clear about its views of thesituation and explain to govern-ments the conditions under whichit would hold interest rates low and

the conditions under which itwould think that higher interestrates would be more appropriate.

The coordination challenge

Economic policy coordination iscontroversial in the EU. The needfor coordination at this junctureshould not be used as a pretext tostrengthen it permanently. Anyattempt to do so could backfire. It

Against the background of weakpublic demand and possibly weak

global demand, this may takesome time. Hence, policy interestrates may have to remain close tozero for an extended period andunconventional initiatives may forthe time being have to remain partof central bankers toolkits.

However, there is a non-negligibledanger that a low interest-rateenvironment could once again fuelbubbles and recreate the condi-

tions that contributed to thefinancial excesses of the early2000s. Already signs haveemerged pointing in this direction.In response, a second policyinstrument for central banks isneeded in addition to the interestrate. We recommend speeding upthe creation of the EuropeanSystemic Risk Board (ESRB),which the European Councilagreed on in June. Ideally, it

should be in place by summer2010. This strengthened macro-prudential supervisory frameworkcould be used inter alia to helptime the phasing in of stricter andanti-cyclical capital buffers forbanks, and to pre-empt the exces-sive leveraging that can accompa-ny bubbles.

Another, politically more delicate,concern is the coordination

required to achieve the desiredsequencing between fiscal andmonetary policy. The difficulty isnot so much that governmentsand central banks would find ithard to agree on the principle thatbudgetary exit should come firstand monetary exit later once infla-tionary pressures are building upagain. However, central banks arereluctant formally to engage in anyform of ex-ante coordination that

-

8/6/2019 pb_exitstrategies_151009_01

8/8

bruegelpolicybrief08

Visit www.bruegel.org for information on Bruegel's activities and publications.

Bruegel - Rue de la Charit 33, B-1210 Brussels - phone (+32) 2 227 4210 [email protected]

A EUROPEAN EXIT STRATEGY

made on the basis of govern-ment debt net of the value of

bank capital held by thegovernment, instead of grossdebt. Firm deadlines should beset for the termination ofgovernment guarantees.

3. Budgetary consolidation shouldstart in 2011 with the with-drawal of the stimulus and con-tinue at a steady pace under a'European Sustainability Prog-ramme' covering 2010-2015.In accordance with this pro-

gramme, each governmentshould present to its parliamentby summer 2010 a medium-term budgetary plan, includinga debt target for end-2014, and

annual minimum and maxi-mum consolidation objectives.

4. The proposed EuropeanSustainability Programmeshould be enforced through theSGP. This may require technicalamendments to SGP pro-cedures to accommodate thetimetable for the exit after sucha severe crisis. Governmentsshould also be encouraged tostrengthen their budgetaryinstitutions, including throughthe establishment of independ-

ent Sustainability Councils.5. Central banks, especially the

ECB, should resist the tempta-tion of premature tightening.Timely budgetary retrenchment

and post-crisis adjustments inthe private sector will weaken

aggregate demand, creatingmore room for monetary policywithout increasing inflationarypressures, though central banksshould be ready to increaseinterest rates to deal withpotential inflationary threats.

6. To avoid the build-up of fin-ancial instability in the contextof exceptionally low short-terminterest rates, preparations forthe creation of the European

Systemic Risk Board, and forthe definition of a macropruden-tial policy framework, shouldspeed up with a view to beingoperational by summer 2010.

REFERENCES:Bernanke, Ben S. (2009) Speech before the Commmittee on Financial Services, US House of Respresentatives, Washington DC, 21July 2009.

Bini Smaghi, Lorenzo (2009) Speech at the Banca dItalia/Bruegel/Peterson Institute conference An Ocean apart: Comparingtransatlantic responses to the financial crisis, Rome, 10-11 September.

Cerra, Valerie and Sweta Saxena (2008) Growth dynamics: the myth of economic recovery, American Economic Review 98(1),

439-457.Cottarelli, Carlo, and Jos Vials (2009) A Strategy for Renormalizing Fiscal and Monetary Policies in Advanced Economies, IMFStaff Position Note 09/22, September.

von Hagen, Jrgen (2009) The monetary mechanics of the crisis, Bruegel Policy Contribution No 2009/08, August.

von Hagen, Jrgen, and Jean Pisani-Ferry (2009) Memo to the Commissioner for Economic and Monetary Affairs, in Andr Sapir(ed) Memos to the new Commission, Bruegel, September.

Hughes Hallett, Andrew, Rolf R. Strauch and Jrgen von Hagen (2001) Budgetary Consolidation in EMU, European CommissionEconomic Paper 148, Brussels.

International Monetary Fund (2009a) World Economic Outlook, April.

International Monetary Fund (2009b) World Economic Outlook, October.

International Monetary Fund (2009c) Global Financial Stability Report: Navigating the Financial Challenges Ahead, October.

Meier, Andr (2009) Panacea, Curse, or Nonevent? Unconventional Monetary Policy in the United Kingdom, IMF Working Paper09/163, August.

Pisani-Ferry, Jean, Philippe Aghion, Andr Sapir, Alan Ahearne, Jrgen von Hagen, Marek Belka and Lars Heikensten (2008)Coming of age: report on the euro area, Bruegel Blueprint 04, January.

Pisani-Ferry, Jean, and Bruno Van Pottelsberghe (2009) Handle with care: Post-crisis growth in the EU, Bruegel Policy Brief No2009/02, April.

Posen, Adam and Nicolas Vron (2009) A solution for Europe's banking problem, Bruegel Policy Brief No. 2009/03.

Trichet, Jean Claude (2009) The ECBs exit strategy, speech, Frankfurt, 4 September.

Bruegel 2009. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted inthe original language without explicit permission provided that the source is acknowledged. The BruegelPolicy Brief Series is published under the editorial responsibility of Jean Pisani-Ferry, Director. Opinionsexpressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone.