Empatía en Parejas

-

Upload

alexandra-torres-de-la-hoz -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

0

Transcript of Empatía en Parejas

-

8/17/2019 Empatía en Parejas

1/9

Understanding the One You Love: A Longitudinal Assessment of an Empathy Training

Program for Couples in Romantic Relationships

Author(s): Edgar C. J. Long, Jeffrey J. Angera, Sara Jacobs Carter, Mindy Nakamoto and

Michelle Kalso

Source: Family Relations, Vol. 48, No. 3 (Jul., 1999), pp. 235-242Published by: National Council on Family Relations

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/585632

Accessed: 05-04-2016 01:50 UTC

R F R N S

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/585632?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

http://about.jstor.org/terms

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted

digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about

JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

National Council on Family Relations, Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve andextend access to Family Relations

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Tue, 05 Apr 2016 01:50:21 UTCAll use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

-

8/17/2019 Empatía en Parejas

2/9

Understanding the One You Love:

A Longitudinal Assessment of an Empathy Training Program

for Couples in Romantic Relationships*

Edgar C. J. Long,** Jeffrey J. Angera, Sara Jacobs Carter, Mindy Nakamoto, & Michelle Kalso

Forty-eight couples in romantic relationships volunteered to participate in a 10-hour empathy training program. The five ses-

sions of the program were briefly described and empirical support was given for each component of the training. Couples were

randomly assigned to either a treatment or wait listed comparison group. Both groups completed the five-week training program

at different times. The change in empathy was assessed by several repeated measures analyses of variance. Scores on three em-

pathy measures improved in both groups over the six month period. A change in the perceptions of a partner's empathy at six

months was positively related to relationship satisfaction at the six month follow-up.

T he marital and premarital literature presently demonstrate

that partner empathy is an important characteristic of a well-

adjusted, stable relationship (Davis & Oathout, 1987; Fran-

zoi, Davis, & Young, 1985; Long, 1990; 1993a, 1993b; Long &

Andrews, 1990). Empathy (perspective taking and empathy will be

used synonymously within the body of this paper), has been defined

as the ability to understand what the other is thinking, put oneself in

the other's place, and intellectually understand another's condition

without vicariously experiencing their emotions (Hogan, 1969).

This line of research clearly indicates that empathy, understanding

the point of view of one's partner, is an important predictor of mari-

tal adjustment and a propensity to divorce for both husbands and

wives (Long, 1993a, 1993b; Long & Andrews, 1990). Individuals

are more likely to have stable, well-adjusted relationships if they

have partners who are capable of expressing empathy. As a result of

this line of research, some marriage therapists have argued for the

need of empathy training for couples in romantic relationships

(Bagarozzi & Anderson, 1989; Long, 1993a, 1993b).

Empathy training programs have been developed for a diver-

sity of groups including: high school and college students (Hatcher

et al., 1994), medical students (Patore, 1995), nursing staff (Herbek

& Yammarion, 1990), and parents (Brems, Baldwin, & Baxter,

1993). However, the authors are aware of no published programs

that have a sole focus on an increased expression of empathy with

a romantic partner. While numerous marital and premarital pro-

grams are available that focus on active listening, communication,

and conflict resolution skills, no other programs are designed

solely to increase partner empathy. For example, the Relationship

Enhancement Program (Guemey, 1988) has one component of the

30-hour training that addresses the skill of empathy. However, the

stated purpose of the nine-step program is to promote the values of

honesty, compassion, and equity in order to improve family rela-

tionships, not increase family empathy. Given the empirical sup-

port for the importance of empathy, and the lack of other empathy

training programs designed for couples in romantic relationships,

the senior author developed an empathy training program (Long,

1995). The purpose of the present study was to provide empathy

instruction to a volunteer group of couples involved in romantic re-

lationships and then assess the effectiveness of that instruction at

the conclusion of and six months following the training.

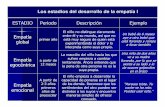

Empirical Rationale and

Program Description by Session

A very brief description of the empathy training program is

provided in the body of this paper. The program was designed as

a structured, psychoeducational group for couples who desired t

increase their expression of empathy with a partner. Like other

training programs, the information was developed to be easy to

understand, free of formal terminology, and relevant to specifi

romantic relationships (Brems et al., 1993). Six components of em-

pathy were described and modeled for participants. The program-

matic ideas and the six components of empathy were develope

through a thorough review of the empathy literature. Several pro-

grams that attempted to teach empathy skills to different popula-

tions were especially useful for the development of this particular

program (Brems et al., 1993; Hatcher et al., 1994; Herbek & Yam

marion, 1990; Patore, 1995). The authors provided empirical sup

port for each of the sessions and components of empathy in th

session descriptions below.

With all of the participants, every effort was made to encour-

age active participation in the training process. Although couple

were not expected to disclose private information about their re

lationships while meeting with the group, they were expected t

complete the homework and discuss issues privately with their

partners. Each of the five, two-hour sessions included a brief lec-

ture about a component of empathy, along with the opportunity

for a large group discussion of the material. Then couples wer

given an opportunity to discuss the expression of that component

of empathy privately, within the context of their own relation

ships. After Session One, each subsequent session began with

rehearsal of the most salient points from the previous meeting to

maintain continuity from week to week.

Session One

During Session One, participants were provided with an

overview of the five-week training, and were asked to complete

informed consent forms. An operational definition of empathy

was given to each of the individuals. Empathy was defined as: (a

an accurate understanding of the situation of a partner, putting

*An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Annual Meeting of The Na

tional Council on Family Relations in Washington, D.C., 1997. We gratefully acknowledg

the valuable contributions of Dr. Phame Camarena who read an earlier version of this paper.

**Address correspondence to: Edgar C. J. Long, Ph.D., Department of Human Env

ronmental Studies, Central Michigan University, Mt. Pleasant, MI 48859; e-mail

Key Words: dyadic perspective taking, empathy, marital and premarital enrichment, rela-

tionship enhancement programs, relationship satisfaction.

(Family Relations, 1999, 48, 235-242)

1999 V48 N 3235

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Tue, 05 Apr 2016 01:50:21 UTCAll use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

-

8/17/2019 Empatía en Parejas

3/9

yourself in his/her shoes, seeing the world from his/her point of

view and (b) communicating that understanding to a partner, thus

increasing the likelihood that one's partner feels understood. The

group then brainstormed a list of personal characteristics of indi-

viduals they knew who were very empathic. For homework, cou-

ples were asked to keep a mental log of people they observed

during the week, other than their partners, who displayed either

very high or very low levels of empathy.

Session Two

At the beginning of Session Two, individuals were asked to

describe people they had noticed during the previous week who

had demonstrated very high or low levels of empathy. The con-

cept of empathic sensitivity was introduced and defined as a skill

in understanding and being aware of and attuned to other people,

even the most subtle forms of nonverbal communication of others.

This discussion of empathic sensitivity was similar to the discus-

sion of emotional sensitivity as defined by Riggio (1989). Couples

were provided with a copy of the seven items from the Emotional

Sensitivity Scale (Riggio, 1989) as a way of illustrating empathic

sensitivity.

To help participants think about their own empathic sensitiv-

ity, the group was shown a video of a couple discussing a relation-

ship problem. However, the volume was turned down so that no

sound was audible, in order to encourage everyone to focus solely

on the nonverbal channel of communication, rather than the ver-

bal content of the message. Participants were encouraged to think

about how sensitive they were to these subtle, nonverbal cues of

others' communication. Based on observations of the video, par-

ticipants were asked to make inferences about the messages they

had observed being sent through the nonverbal channel of com-

munication. The group then discussed their perceptions of the in-

dividuals and the couple's relationship, basing them solely upon

observation of the nonverbal cues on the video tape. Participants

then rated themselves on a scale, indicating how empathetically

sensitive they were to these nonverbal cues of people in general.

The discussion then moved to empathic sensitivity with a

partner. An important part of the present program was understand-

ing those factors that would encourage the expression of empathy

within the context of a specific relationship. Previous research in-

dicated that people may have the ability to be empathic, but fail to

be empathic within the context of a specific relationship (Long &

Andrews, 1990). Davis and Franzoi (1991) differentiate between

the capacity and the tendency to be empathic. A capacity refers to

one's ability to be empathic; however, a tendency refers to the

likelihood of being empathic with another. One can have a capacity

that is not likely to be expressed within the context of a specific

relationship. Throughout the entire empathy training, individuals

were asked to think about those situations that would increase the

likelihood they would express empathy with their partners. The

training attempted to help couples understand and create an envi-

ronment that would encourage the likelihood that empathy would

be expressed with their partners. Thus, participants were also

asked to rate how empathically sensitive they were towards their

partners. The group brainstormed the reasons why it was often

more difficult to be empathetically sensitive with a partner than it

was to be empathetically sensitive with others in general. Individ-

uals were asked to write down a list of those situations where they

would be the most and the least likely to be empathetically sensi-

tive with their partners. Couples were then given private time

with each other to discuss this information. The facilitators were

attempting to encourage couples' understanding of the fact that

empathy is often relationship and situation specific, not expressed

similarly across relationships and situations.

Several scholars have suggested that an important componen

of empathy is the suspension of one's own thoughts and feeling

(Barret-Lennard, 1962; Gladstein & Feldstein, 1983). It is impossi-

ble for an individual to be empathic if that person is overly focused

upon his/her self. One can only express empathy towards a part

ner by focusing on the point of view of the partner, at least tem-

porarily putting one's own point of view aside. Couples were asked

to generate a list of the situations that increase the likelihood o

suspending one's own thoughts and feelings in order to focus

upon the thoughts and feelings of the partner. Partners then

shared this information with each other.

An additional component of empathy is listening (Guerney

1974; Ickes, 1997; Rogers, 1957). Empathic listening was defined

as a situation where a person is consciously, and in a very inten-

tional fashion, attempting to listen to all communicative information

from a partner. The goal of all listening was described as a shared

meaning. A shared meaning is a situation where the message sen

is understood by the listener exactly as it was intended by the

speaker (Miller, Nunally, & Wackman, 1979). To facilitate listening

Egan (1994) suggested that people enact the behaviors within the

SOLER position. Egan suggested that listening was most effectiv

when one faced the person squarely, had open posture, leaned

slightly towards the speaker, had appropriate eye contact, and

practiced these skills in a relaxed fashion.

Couples were asked to discuss with each other how they

would feel if their partner made a concerted effort to be an em-

pathic listener. After couples had completed this assignment in

dyads, facilitators asked couples to share the benefits of empathi

listening with the entire group. Individuals were asked to thin

about those situations in their relationships that were likely to make

empathic listening with their partners happen in a satisfactory man

ner and then communicate that information with their partners.

Finally, a relationship issue was defined as a situation in a re

lationship where a decision needed to be made that concerned on

or both people (Miller et al., 1979). For homework, individual

made a list of the issues they felt needed to be discussed within

their own relationships. Individuals then ranked the severity o

each issue on a seven point scale, indicating how emotionally easy

(0) or difficult (6) it would be to discuss each issue with their part-

ners. During empathy assignments, couples were encouraged t

only discuss issues that were on both partners' lists, and those that

were not too negatively charged with emotion, since they were

learning new skills.

Session Three

Session Three began with a brief talk about gender differences

in communication (Tannen, 1990). Tannen argues that women typi

cally use language to get close to people and join; thus, communi

cation is seen as a way of developing intimacy. On the other hand

males have been socialized to believe that communication is a way

of dominating others and pushing them around. For males, com

munication is often used to protect oneself from others. Severa

scholars indicate that gender differences in communication pat

terns give rise to the pursuer/withdrawal pattern (Gottman, 1994;

Markman, Stanley, & Blumberg, 1994; Notarius, & Markman

1993). Though this pattern does not always hold true, men are

more likely to withdraw from the discussion of relationship issues

236Fm yRton

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Tue, 05 Apr 2016 01:50:21 UTCAll use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

-

8/17/2019 Empatía en Parejas

4/9

whereas women want to pursue the discussion of issues. The facili-

tators then encouraged a large group discussion of this pursuer/

withdrawal situation within the context of participants' own inti-

mate relationships.

Communication, listening, and paraphrasing have long been

perceived as important components of empathy (Rogers, 1957).

One very effective method of helping couples communicate, lis-

ten, and paraphrase is the speaker/listener technique developed

by Markman and his colleagues in the Prevention and Relation-

ship Enhancement Program (Markman, Floyd, Stanley, & Lewis,

1986). This technique has been developed as a way of discussing

relationship issues. The speaker/listener technique involves one

person adopting the role of the speaker while the partner listens

and then paraphrases the content and feelings of the speaker.

Then, individuals change roles. The facilitators presented a video

demonstration of the speaker/listener technique and a couple

trained to use this process modeled the successful use of the tech-

nique. Finally, couples were given time with their partners to

practice the technique. After couples had practiced the speaker/

listener skills, they were asked to evaluate this process and deter-

mine whether or not partners were feeling understood. Any ques-

tions couples had were discussed and answered within the large

group setting. At the end of this session, a homework assignment

was given to couples to select a minor relationship issue and prac-

tice the speaker/listener skill twice during the upcoming week.

Session Four

At the beginning of Session Four, the facilitators introduced

the idea of empathy checking, which is an attempt to assess the

degree to which an empathic understanding had taken place. The

question posed to the speaker was, To what degree was the lis-

tener's paraphrase an accurate understanding of the message

sent? If the listener could communicate the message so that the

speaker felt clearly understood, then empathy had been expressed.

The degree of empathy was demonstrated to the listener on a

bull's eye target. If a message was completely understood, then

the speaker was to point to the bull's eye center of the target. If

the listener did not completely understand the communication,

then the speaker was to point out a location on the target that best

represented the appropriate level of listener empathy. Not arriving

at a complete bull's eye was not initially framed as problematic.

The abilities to communicate and experience an empathic under-

standing were conveyed as difficult processes which took time

and effort. If a complete empathic understanding was not

achieved during the empathy check, then the speaker was to com-

municate the message once again to the listener in an attempt to

assist the listener's arrival at a more accurate empathic understand-

ing. The goal was to achieve the level of empathic understanding

demonstrated by a bull's eye. Individuals were asked to explain to

their partners how it felt when they were fully understood.

Session Five

On the fifth evening, the facilitators reviewed each of the

components of empathy. Again, the facilitators stressed the im-

portance of understanding the situations that make an empathic

understanding more or less likely to happen within the context of

a specific relationship. At this stage of the process, individuals

not only understood the components of empathy, but also the sit-

uations within their own relationships that would make the ex-

pression of empathy more or less likely to take place.

Up to this point in the training, any attempt to solve any rela-

tionship issues had not been made. The sole purpose of the program

was to gain an empathic understanding of the issues. For some cou

ples, this sole focus upon empathy without any attempt to solv

issues in their relationship was frustrating. Thus, in this final ses

sion, once empathy had been demonstrated, the facilitators dis

cussed resolving relationship issues. To solve specific relationshi

issues the facilitators suggested that couples follow four steps

which were an adapted and abbreviated version of the nine-step

Mutual Problem Solving Training (Ridley & Nelson, 1984). Th

four steps were: (a) use all of the empathy skills outlined in the

empathy training program to communicate and listen to each

other; (b) brainstorm as many possible solutions to a situation a

possible; (c) evaluate all of the options and then implement on

possible solution; and (d) set a specific date to evaluate the solu

tion to see if the problematic issue is resolved. If the solution wa

not working by that date, couples were instructed to return to ste

c and attempt another solution.

Method

Participants and Recruitment Procedure

Through newspaper, radio advertisements, and editorials, 4

couples in the central region of Michigan registered to participate

in a five-week, 10-hour empathy training program. Participant

were volunteers who received no compensation for their involve

ment. The advertised goals of the program were to teach individ

uals the skills that were the components of empathic behavior

and then encourage couples to practice those skills with thei

partners. Participants were told that the following six component

of empathy would be taught: empathic sensitivity, suspension o

one's own thoughts and feelings, empathic listening, empathi

communication, the communication of an empathic understand

ing through paraphrasing, and empathic checking with a partner

The average age of the participants was 31.84 years. The partici

pants' ages ranged from 18 through 54 years. Sixteen percent o

the couples were cohabiting, 66% had been married an averag

of 10 years, and 18% had been dating for an average of 21/2 year

The intent of the program was not to assist couples in resolvin

their relationship issues or problems as much as it was to hel

them better express an empathic understanding of each other.

Design

A longitudinal, quasi-experimental design was used to asses

the effectiveness of the training program over time. Pre and post

treatment assessments were undertaken to see if the expression o

empathy with a partner increased over time as a result of the treat-

ment program. Random assignment to either a treatment or wai

listed comparison group was used to control for any pretest differ

ences in empathy that might have existed between the two groups

prior to the empathy training (Kerlinger, 1973). Both groups wen

through the same training at different times. The treatment grou

was trained five weeks before the wait listed comparison group

The authors did not consider it feasible to have a compariso

group that received no treatment at all. Volunteers were all re

cruited based on their interest in empathy training, therefore, th

authors felt ethically obliged to offer the empathy training to a

the volunteers.

Two different groups were in the research design for sever

reasons. Practically speaking, to have 96 people all taking empa

1999 V48 N 3237

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Tue, 05 Apr 2016 01:50:21 UTCAll use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

-

8/17/2019 Empatía en Parejas

5/9

Figure 1. Research Design for Empathy Training

Tm WekI Wek5Wek10Wek24Wek29

Treatmnt Group* Pre-Test Treatmnt Post-Test l) Post-Test 2

(Six month follow-up)

Wit Lsted Comparison Group* Pre-Test Treatmnt Post-Test l) Post-Test 2

(Six month follow-up)

*Couples were randomly assigned to either the treatment or wait listed comparison group. Both groups took the same training at different times. The training was de-

layed for the wait listed comparison group.

thy training at the same time and location would have been very

difficult because the training involved interaction within a large

group as well as interaction between members of the dyad. The

two group design could also be effective in demonstrating a repli-

cation of the results. If both groups received the treatment at dif-

ferent times and scores in both groups increased, it could be

concluded that differences in empathy scores were the result of a

treatment effect and not historical factors outside the training.

The design for the research is represented by Figure 1.

Measures

General empathy of each participant was assessed using the

perspective taking subscale (PT) of the Interpersonal Reactivity

Index (Davis, 1980). The measure was designed to assess the de-

gree to which a person could understand the point of view of others

in general. The measure included items such as, I sometimes try

to understand my friends better by imagining how things look

from their perspective. The PT subscale was a seven item, self-

report measure shown to be stable over time, with adequate inter-

nal consistency and validity (Bernstein & Davis, 1982; Davis,

1980; Davis, Hull, Young, & Warren, 1987). The Alpha coefficient

of reliability with the present sample was .81.

The self-reported expression of empathy with a partner was

assessed using the Self Dyadic Perspective Taking (SDPT) Scale

(Long, 1990). The SDPT was a 13 item, self-report scale which

included items such as, I sometimes try to understand my partner

better by imagining how things look from his/her perspective. An

item analysis and assessments of construct and concurrent validity

indicated that the scale had adequate validity. The Alpha coeffi-

cient of reliability with the present sample was .80.

The perceptions of the expression of empathy of one's own

partner were assessed using the Other Dyadic Perspective Taking

(ODPT) Scale (Long, 1990). The ODPT was a 20 item, paper/

pencil assessment of the empathic expressions of a partner. A sam-

ple item from the scale was, My partner is able to accurately com-

pare his/her point of view with mine. The Alpha coefficient for

the ODPT with the present sample was .94. An item analysis and

assessments of construct and concurrent validity indicated that

the measure had adequate validity.

The propensity for partners to terminate the relationship was

measured with a revised version of the abbreviated Marital Sta-

Table 1

Repeated Measures Analyses of Variance: Change in Empathy Scores Over Six

Months

Scale Time Gender Time * Gender Interaction

PT1129*** 63 867***

SDPT785*** 38 473*

ODPT638 2916

PT: Measure of general perspective taking. SDPT: Measure of self dyadic per-

spective taking. ODPT: Measure of other dyadic perspective taking.

*p

-

8/17/2019 Empatía en Parejas

6/9

perception of partner empathy, the authors hypothesized that indi-

viduals would also perceive an increase in their respective partner's

expression of empathy (ODPT) over the six-month period of time.

As well as the three hypotheses above, an additional ex-

ploratory question was formulated to examine gender differences

on each of the three hypotheses. While females typically score

higher than males on self-report measures of empathy (Eisenberg

& Lennon, 1983), the authors wanted to investigate whether or not

any gender differences in the treatment effect of the empathy train-

ing program would appear. If empathy scores increased over time,

would there be any gender differences in the treatment effect? This

was merely an exploratory question, as no previous empirical work

on which to formulate any directional hypotheses was available.

Hypothesis Four: Since empathy had been positively related

to relationship satisfaction in previous studies (Long, 1993a; Long

& Andrews, 1990), the authors hypothesized that a positive

change in the expression of empathy with a partner over five

weeks and six months would be positively related to relationship

satisfaction at five weeks and six months. Any improvement in the

expression of empathy would be assumed to be related to higher

relationship satisfaction. Hypothesis Five: Since empathy had been

negatively related to a propensity to terminate a relationship in

previous empirical work (Long, 1993a; Long & Andrews, 1990),

changes in empathy at five weeks and six months were predicted

to be negatively related to a propensity to terminate the relation-

ship at five weeks and at six months.

Results

As mentioned above, couples were randomly assigned to either

a treatment or a wait listed comparison group. However, three

couples could not attend the group they had been randomly as-

signed to because of schedule conflicts. As a result of a need for

participants, the authors allowed these couples to participate in

the program and attend the group they had not been assigned to.

The authors did a series of analyses examining any possible em-

pathy differences between the wait listed comparison and treat-

ment groups' empathy scores before the training began. These

analyses were necessary because of the assignment problem

mentioned above, because the sample size was relatively small,

and because random assignment cannot guarantee equal groups.

A series of ANOVA's were used to examine pre-training group

differences on all three empathy measures, general empathy with

others (PT), self-reported empathy with one's partner (SDPT),

and, finally, one's perceptions of a partner's empathy (ODPT).

No significant differences between the treatment and wait listed

comparison group scores on any of the three empathy measures

were found. Thus, the authors could say with certainty that both

groups' empathic abilities, as measured by the three empathy

scales, were equal before the training began.

Treatment Effect of the Training

Changes in general empathy over time. The statistic used to

test for a significant change in empathy scores over six months was

a repeated measures analysis of variance. A significant change in

scores over the six-month period of time was found on the general

empathy scale (PT). No differences in this effect by group were

shown; both the treatment and wait listed comparison group scores

improved over time. Since no differences were evident by group

on any of the three empathy measures, the group variable was not

included in the table of results. Hypothesis One was rejected be-

Figure 2. Changes in PT Means Over Time by Gender

3.8 -

36- Feme

34- a - Mes

; 32 -

3- X

123

Time of Measurement

Time of Measurement 1 = Pre-test (before the training)

Time of Measurement 2 = Five weeks (at the end of the training)

Time of Measurement 3 = Six months (six months following the training)

PT: Measure of general perspective taking

cause over the six-month period the participants' scores on th

general expression of empathy increased. No gender differences in

the increase in the general empathy scores were shown. Male

and females improved equally as a result of the training. How

ever, a time by gender interaction on the general expression o

empathy with others was demonstrated. Thus, the change over

time was unique by gender.

Changes in self-reported empathy with one's partner ove

time. On the self-reported expression of empathy with a partner

(SDPT), a significant change in the scores over time was demon

strated. Once again, no differences by group on the SDPT wa

shown; both the treatment and wait listed comparison group scores

increased over time. Thus, over the six-month time period, all par-

ticipants stated that they had improved the expression of empathy

with their partners. Hypothesis Two was, therefore, supported. Th

analyses also revealed no gender differences on the increase in the

SDPT scores. Males' and females' self-reported expressions o

empathy both increased as a result of the training. However, a tim

by gender interaction effect was evident. Thus, again, the change

over time was unique by gender, as evidenced in figure 3.

Changes in perception of partner's empathy over time. A sig

nificant change in the perceptions of a partner's empathy (ODPT)

over time was indicated. No differences by group on the ODPT

were evident; both the wait listed comparison and treatment group

scores on the ODPT improved over time. Over the six-month

period, all the participants reported an increase in their partner's

expression of empathy. Hypothesis Three was also supported

Once again no gender differences in the changes in the ODPT

scores were found. Both males' and females' scores improved as

result of the training. On the ODPT no time by gender interaction

effect was demonstrated.

Figure 3. Changes in SDPT Means Over Time by Gender

2.8 -

6 - 4 Femes

2.4 -~ - U Mles

L-

22

123

Time of Measurement

Time of Measurement 1 = Pre-test (before the training)

Time of Measurement 2 = Five weeks (at the end of the training)

Time of Measurement 3 = Six months (six months following the training)

SDPT: Measure of self dyadic perspective taking

1999 V48 N 3239

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Tue, 05 Apr 2016 01:50:21 UTCAll use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

-

8/17/2019 Empatía en Parejas

7/9

Figure 4. Changes in ODPT Means Over Time by Gender

2.4 -

2 3

> 22 - /, * *-Femes

21- -0Mes

0 2- *

1.9 - I l l__ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

123

Time of Measurement

Time of Measurement 1 = Pre-test (before the training)

Time of Measurement 2 = Five weeks (at the end of the training)

Time of Measurement 3 = Six months (six months following the training)

ODPT: Measure of other dyadic perspective taking

Empathy change and relationship outcome measures. To test

Hypotheses Four and Five empathy difference scores were calcu-

lated for all participants. For example, a difference score was cal-

culated for the general measure of empathy by subtracting the PT

score at the end of the five-week training (post-test 1) from the

pre-test PT score. This PT difference score (PT5) was then used as

a measure to demonstrate the degree of improvement in the gen-

eral expression of empathy with others during the five week pro-

gram. Another difference score was calculated for each individual

by subtracting the PT score at the end of six months (post-test 2)

from the pre-test PT score. This difference score (PT6) was used

as a measure of the individuals' increased expression of empathy

with others in general at the end of six months. Similar difference

scores were developed for the SDPT SDPT5, SDPT6) and

ODPT (ODPT5, ODPT6) measures. Thus, six difference scores

were calculated for each individual, two for each of the three em-

pathy measures. The first difference score indicated the change in

empathy from the beginning to the end of the five-week training

program. The second difference score demonstrated changes in

empathy through the six-month follow-up.

Each of these difference scores were then correlated with re-

lationship satisfaction and propensity to terminate the relationship

scores. A series of correlation coefficients were calculated to test

these hypotheses. When all participants were examined, only the

change in the ODPT over six months (ODPT6) was significantly

related to relationship satisfaction at the six-month follow-up.

The ODPT6 score was positively related to the global measure of

relationship satisfaction score at the six-month follow-up (r = .39,

p < .05). Thus, for all participants, changes in the perceptions of

their partners' expression of empathy six months after the training

were positively related to their own relationship satisfaction at the

six-month follow-up. Fifteen percent of the variance in relationship

satisfaction at the six-month follow-up was related to the percep-

tion of their partner's change in empathy. None of the difference

scores were significantly related to a propensity to terminate the

relationship. Therefore Hypothesis Four was supported and Hy-

pothesis Five was rejected.

Discussion and Conclusion

The authors believe this study adds to the empirical literature

on the study of empathy. To this point in time, numerous pro-

grams have been designed to teach empathy to a variety of popu-

lations. However, this is the only program the authors are aware of

that has a sole focus on an increased expression of empathy with

a romantic partner. The program shows promise in this first assess-

ment, as participants in both the treatment and wait listed compar-

ison groups had increased scores on all three empathy measures.

Surprisingly, the present study was able to demonstrate

treatment effect in the expression of empathy with others in gen

eral. This was evidenced even though the purpose of the program

was solely to increase empathy with a partner. Subjects in thi

study reported that their new empathic understanding was general-

ized to relationships outside of the relationship with their romantic

partners. The self-report of empathy with others increased for both

males and females. In this culture, empathy is a behavioral expec

tation for females more than it is for males; thus, one might expec

females to generalize their new empathy skills to other relation

ships more than males. However, having highlighted the impor

tance of empathy within relationships, both genders realized th

importance of empathy within the context of relationships and re-

ported they were more empathic with others in general.

As expected, an increase in the self-reported expression of em

pathy with a partner and an increase in the perception of one's part

ner's empathy were demonstrated. Males and females both rate

themselves as being more empathic and rated their partners a

more empathic over the six-month period. For a time, social scien

tists debated whether or not people could learn to be more em

pathic with others (Myrick & Erney, 1985). This study, however

adds to a growing body of literature that demonstrates that empa-

thy can, indeed, be learned. Even within the context of intimate re-

lationships, people can learn to express greater empathy toward

their partners. Even in a culture where males are often not expected

to be as empathic as females, males can learn to be more empathic.

The increase in empathy scores at six months for both genders

is an important finding within this study. Since the program doe

demonstrate a change in empathy, the authors were encouraged to

see that the change could be measured at the time of the secon

post-test. As noted above, the authors attempted to make the pro-

gram easy to understand and relevant. The fact that the change in

empathy scores could be measured at six months may be an indica-

tion that the program achieved the goals of ease and relevance. Fu-

ture research would do well to assess the effect of the program for

an even longer period of time, so that interventionists can decid

when couples may need a booster training session.

The interaction effects noted in these analyses need clarifica-

tion in future research. For both the self-report PT and SDPT

scales, the pattern of change over time was different by gender.

The time by gender interaction effect denotes the importance o

gender change over time. As indicated in figure two, the change in

empathy scores during the first five weeks was more pronounced

for females than males. When asked about their own general em-

pathic abilities, females were more likely than males to report

more rapid response to the training. While gender difference in

scores were not demonstrated, the change over time was uniqu

by gender. Future research would do well to assess the reason and

extent of that gender change in scores over time.

Also important is the fact that the change in empathic expres-

sion with a partner was positively related to relationship satisfac-

tion. The increased expression of empathy over six month

accounted for 15% of the relationship satisfaction six months fol-

lowing the training. The change in the expression of empathy a

five weeks was not significantly related to satisfaction at five

weeks but only after six months. Perhaps both males and female

were waiting to see if their partners' empathy change would las

over time. Had one's partner really changed or did a 10-hour pro-

240Fm yRton

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Tue, 05 Apr 2016 01:50:21 UTCAll use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

-

8/17/2019 Empatía en Parejas

8/9

gram only temporarily influence the expression of empathy? The

results indicated that by six months those who truly perceived their

partners as more empathic were also more likely to have higher

levels of relationship satisfaction. Since partner empathy has been

previously shown to be positively related to relationship satisfac-

tion, one would expect this finding. This finding again verified the

importance of empathy within the context of intimate relationships.

When individuals improve their empathic abilities, partners' rela-

tionship satisfaction improves.

The authors expected that increased empathy would also be

negatively related to thoughts about terminating the relationship.

When individuals improve their empathic abilities, partners would

be less likely to leave the relationship. However, increased expres-

sion of empathy was not related to fewer thoughts about leaving

the relationship. For the most part, couples in this study were in

long term relationships. On the average, the married couples had

been together 10 years and the dating couples 21/2 years. Perhaps

therapists and marriage scholars should not expect a change in

the expression of empathy to quickly influence people's thoughts

about terminating a relationship. Other empirical work does indi-

cate that the process of relationship disaffection takes a consider-

able amount of time (Kayser, 1996). Thus, more than a six-month

period may be necessary for the expression of empathy to make

significant changes in people's thoughts about leaving or staying

in a relationship. Future researchers should examine changes in

empathy for a time period greater than six months.

A gender difference noted within this sample that contrasts

with previous empirical work was the fact that, at the pre-test, fe-

males did not have significantly higher scores than males on all

three empathy measures. Historically, females' scores on self-report

measures of empathy have typically been higher than males' scores

(Eisenberg & Lennon, 1983). Why does this sample demonstrate a

difference? Perhaps the type of males who agreed to be involved in

this program already were more empathic than males in the general

population. If that is the case, this type of a program may only be

assisting males who are already more empathic than average males

in the population.

Future research also needs to examine the relationship char-

acteristics of those most likely to participate in an empathy enrich-

ment program and the relationship characteristics of those most

and least likely to improve their skills during such a program.

During discussions with couples the facilitators realized that pre-

existing levels of relationship conflict seemed to impede some

couples' ability to respond empathetically to each other. Perhaps

high levels of conflict within a relationship at the outset of a pro-

gram may diminish the desire to express empathy with a partner,

regardless of one's empathic ability. Individuals in these troubled

relationships may feel angry or frustrated that a partner does not

understand their needs for affection, sex, or caring, thus their mo-

tivation to express empathy with a partner might be weak. From

this point of view, expressing empathy to a partner may be highly

unlikely, even with adequate empathy skills. In this troubled rela-

tionship situation, a partner may be more likely to seek to change

or hurt the other partner, with little desire to understand one's part-

ner's point of view. Coming into empathy training in this condi-

tion, the person may not be as motivated to express empathy as

are those individuals who come without a history of relationship

problems. These questions should be examined in future research.

Limitations of the Study

Several limitations within the design of this study need to be

understood when interpreting the results of this work. First, the

sample of couples for this study was a volunteer sample of people

who responded to newspaper advertisements and radio editorials

These findings may not generalize to a cross section of people in

intimate, heterosexual relationships who would not volunteer t

be involved in such a program. In what way does the uniquenes

of these volunteer couples influence the results of this program

A definitive answer to this question cannot be given at this time

This type of program may be too time and energy intensive for

some individuals. The largest number of couples discontinued th

training after the first session when they realized the time com

mitment involved. For the program to be effective, couples mus

be willing to invest a sufficient amount of time and energy. Futur

research needs to examine the relationship and individual charac

teristics of those willing and unwilling to invest five weeks in th

improvement of their relationships.

As is true with any longitudinal design, attrition of partici

pants was a problem with the current study. Several subjects wh

completed the program and the five week assessment had moved

and could not be located at the six-month follow-up. The author

have no way of knowing whether or not the results would chang

if these participants were included in the six-month follow-up data

Evaluation researchers also suggest that programs be evalu

ated and compared to alternate treatment programs (Guerney

Maxson, 1990). Since this was the initial assessment of the empathy

training program, we believe the design implemented was appro

priate for this stage of program evaluation. However, future research

would do well to compare this empathy training program with

the relationship outcomes of individuals who have taken othe

programs such as PREP (Markman et al., 1986), the Relationship

Enhancement Program (Guerney, 1974), or have been involved in

individual counseling to improve empathy with a partner.

References

Bagarozzi, D. A., & Anderson, S. A. (1989). Personal, marital and family myths

Theoreticalformulations and clinical strategies. New York: Norton & Company

Barrett-Lennard, G. T. (1962). Dimensions of therapist response as causal factor

in therapeutic change. Psychological Monographs, 43, 185-193.

Bernstein, W. H., & Davis, M. H. (1982). Perspective taking self-consciousness an

accuracy in person perception. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 3, 1-19.

Booth, A., Johnson, D., & Edwards, J. N. (1983). Measuring marital instability

Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45, 387-394.

Brems, D., Baldwin, J., & Baxter, S. (1993). Empirical evaluation of a self

psychologically oriented parent education program. Family Relations, 42, 26-30.

Davis, M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in

empathy. Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 10, 85.

Davis, M. H., & Franzoi, S. L. (1991). Stability and change in adolescent self

consciousness and empathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 25, 70-87.

Davis, M. H., Hull, J. G., Young, R. D., & Warren, P. (1987). Emotional reac

tions to dramatic film stimuli: The influence of cognitive and emotional em

pathy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 126-133.

Davis, M. H., & Oathout, H. A. (1987). Maintenance of satisfaction in romanti

relationships: Empathy and relational competence. Journal of Personality an

Social Psychology, 53, 397-410.

Egan, G. (1994). The skilled helper: A problem-management approach to help

ing. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing.

Eisenberg, N., & Lennon, R. (1983). Sex differences in empathy and related ca

pacities. Psychological Bulletin, 94, 100-13 1.

Franzoi, S. L., Davis, M. H., & Young, R. D. (1985). The effects of private self

consciousness and perspective taking on satisfaction in close relationship

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 1584-1594.

Gladstein, G. A., & Feldstein, J. C. (1983). Using film to increase counselor em

pathic experiences. Counselor Education and Supervision, 20, 125-131.

1999 V 48 N 3241

This content downloaded from 168.176.5.118 on Tue, 05 Apr 2016 01:50:21 UTCAll use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

-

8/17/2019 Empatía en Parejas

9/9

Glenn, N. D. (1990). Quantitative research on marital quality in the 1980s: A

critical review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 818-831.

Gottman, J. M. (1994). What predicts divorce: The relationship between marital

processes and marital outcomes. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Guerney, B. G. (1974). Relationship enhancement: Skill-training programs for

therapy, problem prevention, and enrichment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Guerney, B. G. (1988). Family relationship enhancement: A skill training ap-

proach. In L. A. Bond, & B. M. Wagner, (Eds.), Families in transition: Pri-

mary prevention programs that work. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Guerney, B. H., & Maxson, P. (1990). Marital and family enrichment research: A

decade review and look ahead. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 1127-

1135.

Hatcher, S. L., Nadeau, M. S., Walsh, L. K., Reynolds, M., Galea, J., & Marz, K.

(1994). The teaching of empathy for high school and college students: Testing

Rogerian methods with the interpersonal reactivity index. Adolescence, 29,

961-974.

Herbek, T. A., & Yammarion, F. J. (1990). Empathy training for hospital staff

nurses. Group and Organization Studies, 15, 279-295.

Hogan, R. (1969) Development of an empathy scale. The Journal of Consulting

and Clinical Psychology, 33, 307-316.

Ickes, W. (1997). Empathic accuracy. New York: Guilford.

Kayser, K. (1996). The marital disaffection scale: An inventory for assessing

emotional estrangement in marriage. American Journal of Family Therapy,

24, 83-88.

Kerlinger, F. N. (1973). Foundations of behavioral research, (2nd ed.). New York:

Holt, Rhinehart and Winston.

Long, E. C. J. (1990). Measuring dyadic perspective taking: Two scales for as-

sessing perspective taking in marriage and similar dyads. Educational and

Psychological Measurement, 50, 91-103.

Long, E. C. J. (1993a). Maintaining a stable marriage: Perspective taking as a

predictor of a propensity to divorce. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 21,

121-138.

Long, E. C. J. (1993b). Perspective taking differences between high and low ad-

justment marriages: Implications for those in intervention. American Journal

of Family Therapy, 21, 248-260.

Long, E. C. J. (1995). Empathy training program for couples in romantic rela-

tionships. Unpublished Manuscript.

Long, E. C. J., & Andrews, David, W. (1990). Perspective taking as a predictor of

marital adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 126-13 1.

Markman, H. J., Floyd, F., Stanley, S., & Lewis, H. (1986). Prevention. In N. Ja-

cobson & A. Gurman (Eds.), Clinical handbook of marital therapy (pp. 174-

194). New York: Guilford.

Markman, H. J., Stanley, S. M., & Blumberg, S. L. (1994). Fighting for your

marriage: Positive steps for preventing divorce and preserving lasting love.

San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Miller, S., Nunally, E. W., & Wackman, D. B. (1979). Couple communication I:

Talking together. Minneapolis, MN: Interpersonal Communication Programs Inc.

Myrick, R., & Erney, T. (1985). Youth helping youth: Becoming a peerfacilitator.

Minneapolis, MN: Educational Media Corporation.

Notarius, C., & Markman, H. (1993). We can work it out: Making sense out o

marital conflict. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons.

Patore, F. (1995). Empathy training course packetfor medical students. Valhalla

NY: New York Medical College.

Ridley, C. A., & Nelson, R. B. (1984). The behavioral effects of training premar

ital couples in mutual problem-solving skills. Journal of Social and Persona

Relationship, 1, 197-210.

Riggio, R. E. (1989). Social skills inventory manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consultin

Psychologists Press.

Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic per

sonality change. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 21, 95-103.

Sharpley, C. F., & Cross, D. G., (1982). A psychometric evaluation of th

Spanier Dyadic Adjustment Scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 44

739-741.

Spanier, G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing

the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family

38, 15-27.

Tannen, D. (1990). You just don't understand: Women and men in conversation

New York: Morrow.

Edgar C. J. Long, Ph.D., is Professor of Family Studies and Direc

tor of the Honors Program at Central Michigan University.

Jeffrey J. Angera, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Counseling a

Central Michigan University.

Sara Jacobs Carter is a graduate of Central Michigan University

Family Studies Program and is a graduate student at Arizona Stat

University in Marriage and Family Therapy.

Mindy Nakamoto is a graduate of Central Michigan University

Family Studies Program and is a graduate student at University o

Minnesota in Family Science.

Michelle Kalso, is a graduate of Central Michigan University Fam

ily Studies Program and is employed by Families First in Detroit

Michigan.

Received 6-6-1998

Revised & Resubmitted 1-18-1999

Accepted 5-10-1999

Prices Slashed on Excellent Textbook Supplement

T his volume addresses matters of

vital importance to families: to IN-DEPTH INFORMATION FOR GRANT

family professionals who work in AND PROPOSAL PREPARATION

the areas of teaching, research, interven-

tion, and policy; and to those interested

in adolescents. It draws on research and

theoretical thinking of the authors of

23 select articles to create a valuable David H. Demo and Anne-Marie Ambert Editors

resource and an exciting text. The authors J A

. . . ~~~~~~~~~~~~Jay A. Mancini, Senior Editor

examine the intersection of adolescent

developmnt and the famly system NCFR Member $@5 $27.95

280 pages. ISBN 0-916174-51-4. Non-Member 9i95 $31.95

Product #: OP9508 To order, contact NCFR, 3989 Central Ave., NE, Ste. 550, Minneapolis, MN 55421.

t __________________________ _I Toll-free at 888-781-9331; Fax: 612-781-9348; E-mail: ncfr3989gncfr.org.

242Fm yRton

Thi t t d l d d f 168 176 5 118 T 05 A 2016 01 50 21 UTC